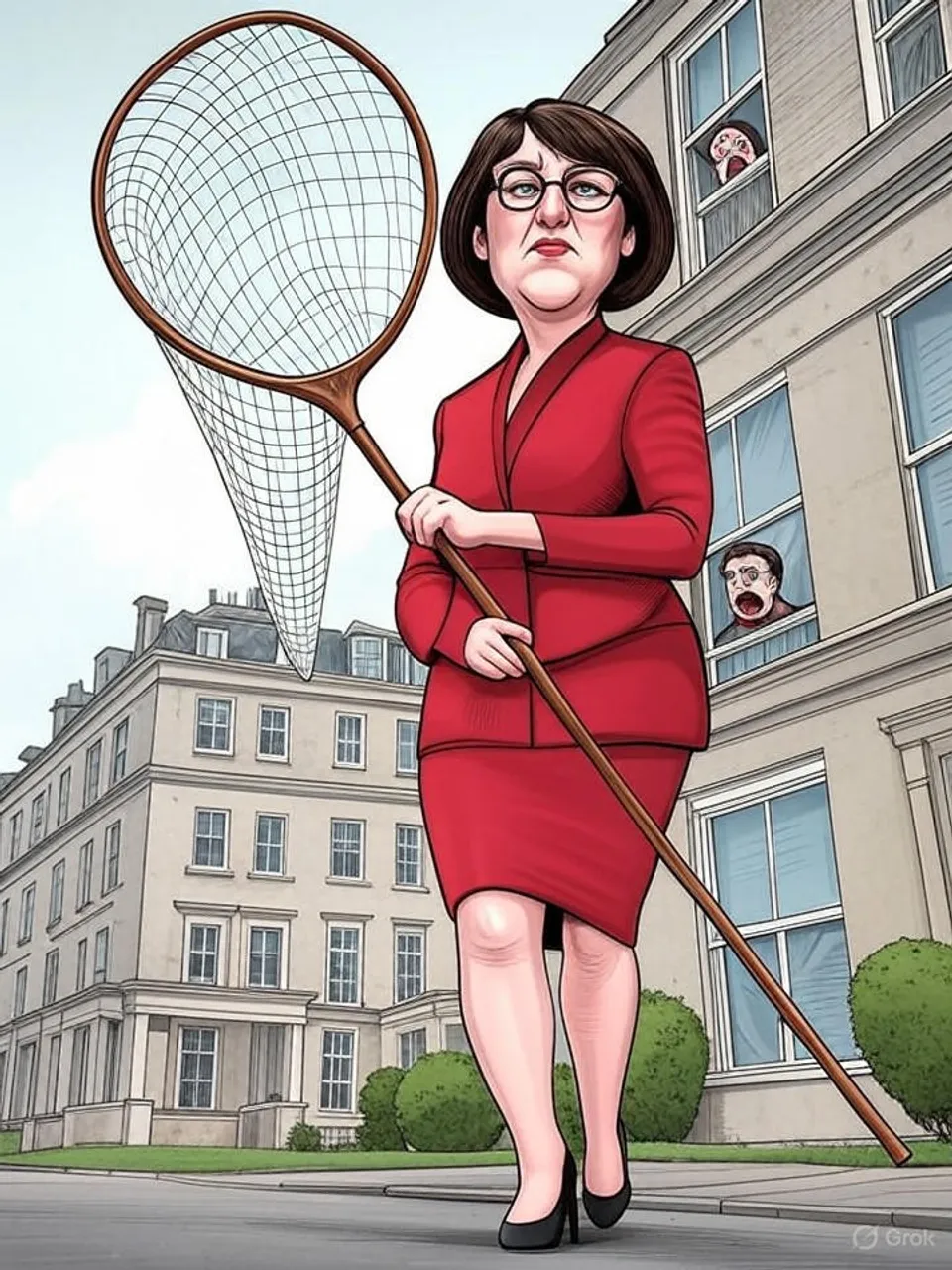

1991 Bands Snare £135,000 Homes in Reeves's Levy

Outdated valuations turn modest northern properties into tax targets

Rachel Reeves's proposed mansion tax relies on 1991 council tax bands, hitting £135,000 homes in the north while sparing million-pound southern ones in lower categories. This exposes systemic unfairness and cross-party neglect of tax reform.

Commentary Based On

GB News

'Mansion tax' shock as homes worth just £135,000 could be hit under Rachel Reeves's Budget plans

Rachel Reeves targets council tax bands F through H for a new property levy, but properties valued at just £135,000 in northern England now qualify for scrutiny. Officials brand it a “mansion tax,” yet the measure ensnares one in ten English homes, including modest three-bedroom houses owned by pensioners. This gap exposes how fiscal desperation warps targeted policy into broad-based extraction.

The council tax system, frozen since 1991, allocates bands based on valuations from that era. A Band F property then ranged from £120,001 to £160,000, but inflation and regional booms have distorted outcomes. In Manchester and Solihull, Band F homes sell for £135,000 today; in north London, equivalents fetch £2.9 million.

PropertyData analysis reveals the absurdity. Band F spans £135,000 to £2.9 million within the same category, creating postcode lotteries. Meanwhile, a £2.9 million home in Worcester sits in Band E and escapes revaluation entirely.

Reeves plans to revalue only higher bands, adding a surcharge on about 300,000 properties collected by HMRC. The threshold hovers uncertainly at £1.5 million or £2 million, leaving 2.4 million households in limbo. This selective approach ignores lower-band anomalies, like million-pound London properties.

Regional Disparities Amplify Unfairness

Northern homeowners bear the brunt. A Birmingham Band F house under £150,000 faces potential hikes, while southern equivalents in lower bands do not. Michael Dent of PropertyData calls this variation “astonishing,” rooted in three decades of uneven growth.

David Edwards, a 72-year-old in Greater Manchester, owns a £400,000 three-bedroom home classified as Band F. He and his wife, both pensioners, live modestly without luxuries. Their fixed incomes now risk erosion from a levy misnamed for mansions.

Experts like Chris Ball question enforcement. Defining a “mansion” varies by location—a London flat might cost what a northern house does. Linking the tax to outdated bands invites chaos, especially for elderly owners on state pensions.

Fiscal Pressures Drive Hasty Design

The Budget on November 26 aims to plug a £22 billion hole, with Reeves eyeing taxes on the wealthy. Yet this levy shifts burdens downward. It follows patterns of stealth taxation, like recent EV bay rates and pension raids.

No comprehensive revaluation has occurred since 1991, despite Labour and Conservative governments alike. Both parties deferred updates to avoid backlash, entrenching inequities. The result: a system that punishes regional stagnation while sparing urban wealth in misaligned bands.

This proposal reveals deeper institutional decay. Tax policy, meant to fund public services, instead perpetuates 1990s relics amid crumbling infrastructure. Ordinary citizens, not elites, absorb the costs of political inaction.

Homeowners now scramble for valuations and sales timing. Trusts offer mitigation but trigger immediate taxes. The uncertainty alone chills markets, as 2.4 million households await clarity.

The levy underscores Britain’s fiscal sclerosis. Outdated mechanisms extract from the vulnerable while evading true reform. Across governments, the same avoidance of hard choices burdens working families, accelerating economic stagnation and eroding trust in equitable governance.

Commentary based on 'Mansion tax' shock as homes worth just £135,000 could be hit under Rachel Reeves's Budget plans at GB News.