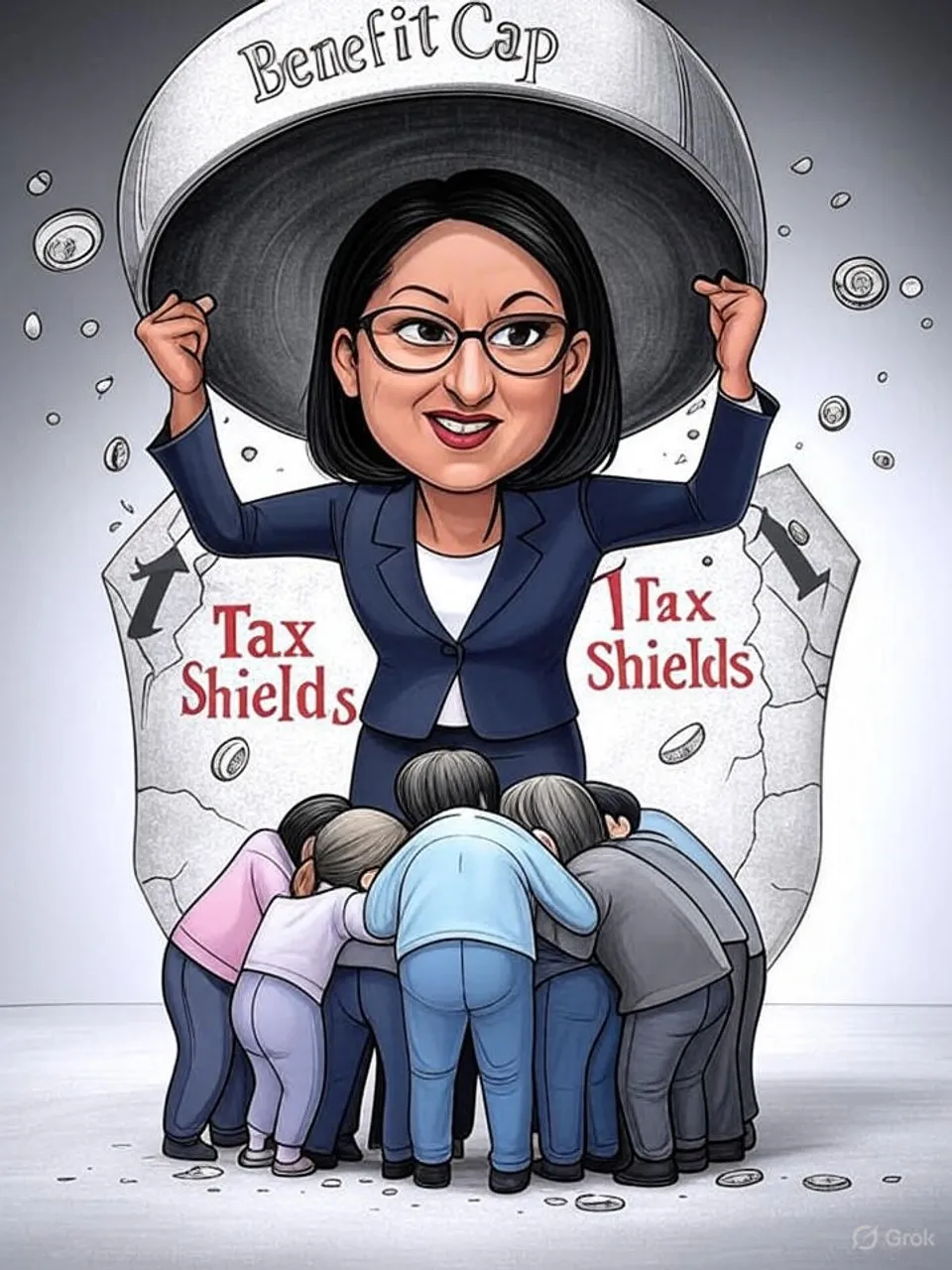

Benefit Caps Lift, But Tax Shields Crack

£3.6 Billion to Free 630,000 Children from Poverty

Rachel Reeves plans to scrap the two-child benefit limit, easing child poverty at a steep cost that forces breaches of Labour's tax pledges. This trade-off exposes ongoing fiscal fragility across governments.

Rachel Reeves signals an end to the two-child benefit cap, a policy that has locked 630,000 children in poverty since 2017. This reversal promises to ease hardship for larger families but demands £3.6 billion annually from public coffers. The move exposes the chancellor’s readiness to breach Labour’s manifesto pledges on taxes, trading one fiscal pressure for another.

The two-child limit bars working-age households from universal credit or child tax credit payments for third or subsequent children born after April 2017. Introduced by the Conservatives to curb welfare costs, it affects over 400,000 families today. Official data shows it deepened absolute poverty, defined as incomes below 60% of the median, even as child benefit persists for higher earners up to £80,000.

Reeves frames the policy as unfair punishment for children in bigger families. She cites changing financial circumstances that lead parents to have three or four children. Yet this overlooks how the cap stemmed from broader austerity measures that squeezed public spending across governments.

Labour’s 2024 manifesto vowed no increases in income tax rates, National Insurance, or VAT. Reeves now hints at abandoning these commitments, noting that adhering to them would require deep cuts in capital spending. She prioritizes NHS funding and waiting list reductions, refusing to apologize for the trade-offs.

Freezing income tax thresholds beyond 2028 remains on the table. This “fiscal drag” pulls more earners into higher bands as wages rise, effectively raising taxes without rate changes. The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates this could generate billions, but it burdens low- and middle-income workers who form Labour’s base.

The Treasury has explored alternatives, like tapered benefits that pay more for the first child and less for others. Options included limits up to three or four children. Reeves rejects size-based restrictions outright, aligning with calls from Labour MPs like Lucy Powell and Bridget Phillipson during the deputy leadership contest.

Past Labour governments cut child poverty by 600,000 between 1997 and 2010 through targeted investments. Current levels stand at 4.3 million children, a figure that rose under both Coalition and Conservative rule. Reversing the cap could mirror those gains, but only if sustained funding follows.

Fiscal reality undercuts the optimism. Reeves inherited unfunded commitments from the previous government, including spending review pledges. Her June announcements added billions to public sector budgets, now compounded by benefit expansions.

The Conservatives defend the cap, arguing welfare recipients should face the same choices as working families. Reform UK proposes scrapping it only for “working British couples.” These positions highlight partisan divides, but the underlying issue—welfare costs versus tax relief—persists regardless of party.

Child poverty extracts long-term costs: lower educational outcomes, higher NHS demands, and reduced productivity. The £3.6 billion to lift the cap equals a fraction of the £50 billion public finance gap Reeves faces. Yet without addressing wage stagnation or housing shortages, such measures treat symptoms, not causes.

Institutions across governments have failed to break this cycle. Policies like the 2013 overall benefit cap and the 2017 two-child limit aimed to control spending but entrenched deprivation. Officials promise reductions, deliver partial fixes, then shift burdens to taxpayers.

Reeves’ approach reveals power’s true mechanics: manifesto pledges bend under economic strain. Labour MPs pressured for change, but the public foots the bill through higher taxes or frozen thresholds. Ordinary families gain short-term relief while systemic weaknesses—decades of underinvestment and policy flip-flops—deepen the divide.

This episode underscores Britain’s entrenched decline. Anti-poverty efforts demand fiscal contortions that erode trust in governance. Larger families may see benefits rise, but the nation’s capacity to deliver without penalty shrinks, leaving citizens to navigate a welfare state strained by repeated political compromises.

Commentary based on Rachel Reeves suggests family benefit limits will be lifted at BBC News.