The Steel Trap: How Brexit Britain Became Europe's Industrial Afterthought

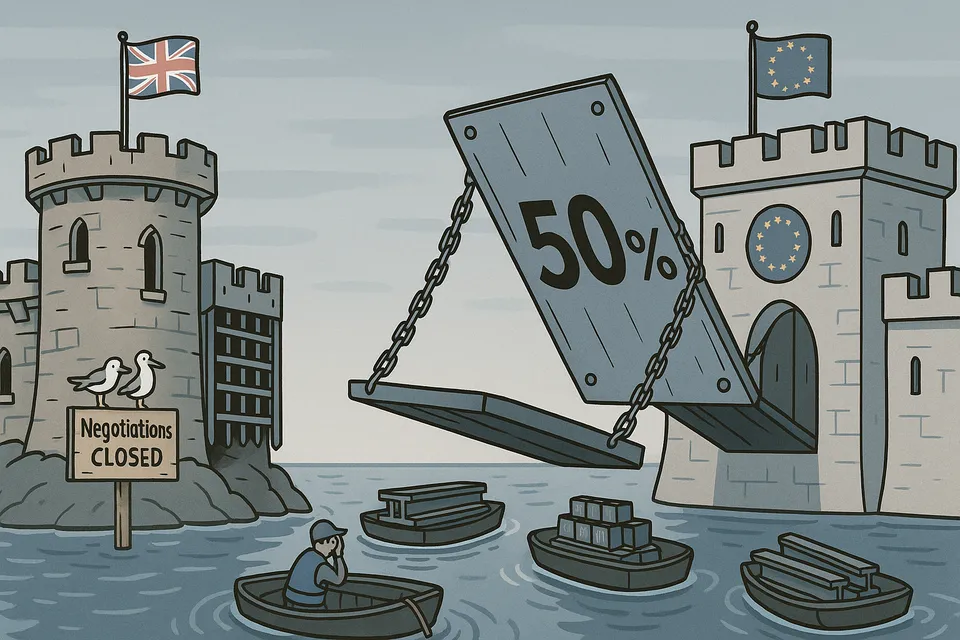

Why the EU's 50% Steel Tariffs Spell Disaster for UK Industry

Importing twice the steel it produces, relying on EU buyers for 78% of exports, and having no negotiated protections, Britain faces an 'existential threat' to its steel industry after the EU imposed 50% tariffs. This article explores the institutional failures and economic realities behind this crisis.

Commentary Based On

The Guardian

‘Existential threat’: what do EU’s 50% steel tariffs mean for UK industry?

On Tuesday, the European Union announced 50% tariffs on steel imports. Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein received automatic exemptions. The United Kingdom did not.

This matters because 78% of British steel exports go to the EU. That’s 1.9 million tonnes of metal that just became uncompetitive overnight. The UK steel industry now faces what insiders are calling an “existential threat.” They are not exaggerating.

Britain imports twice the steel it makes. It depends heavily on European buyers for what it does produce. And despite years of Brexit negotiations and promises of new trade arrangements, the government appears to have secured precisely nothing to protect this critical industrial sector when the tariffs arrived.

The Context

In 1973, Britain joined the European Coal and Steel Community, gaining seamless access to continental markets. For 47 years, UK steelmakers operated within an integrated single market. They built supply chains, customer relationships, and business models around that access.

In 2016, voters were told leaving the EU would free Britain to strike better trade deals and strengthen British industry. In 2020, the UK formally left. In 2025, British steel faces effective lockout from its primary market while countries that stayed in the European Economic Area remain protected.

The government’s response so far: tell the industry to “push for country-specific carve-outs.” This is not a strategy. This is begging for special treatment Britain deliberately gave up the institutional mechanisms to secure.

The Evidence

The numbers reveal the trap Britain built for itself:

Market Reality: The EU accounted for £3.2 billion in UK steel exports in 2024. Ireland, still in the single market, is the biggest individual buyer. The sixth-largest destination is the United States, where Trump’s 25% tariffs already apply after the UK-US zero-tariff deal collapsed.

Production Capacity: British steelworks, already struggling with Europe’s highest energy costs, cannot simply redirect output elsewhere. The global market is flooded with cheap Chinese steel. Non-EU buyers are few. The government promises to direct spending on warships and railways to British steelworks, but Britain imports twice what it produces. Domestic demand alone cannot sustain the sector.

Political Position: Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein remain integrated into the single market through the EEA. They face no tariffs. Britain chose to leave all such arrangements. It now has no institutional leverage, no guaranteed quota, and no automatic protections.

Timeline Failure: EU safeguard measures were set to expire in June 2026. Trump imposed 50% US tariffs in June 2025. The trajectory was clear for months. Yet UK steelmakers learned of the EU decision when Brussels announced it publicly. There was no advance negotiation, no contingency plan, no secured access.

The Pattern

This follows a familiar sequence in post-Brexit Britain:

Stage One: Leave the institutional framework that provided market access and regulatory influence.

Stage Two: Discover that other countries now treat Britain as a third country, not a special partner.

Stage Three: Express surprise that agreements negotiated as an EU member no longer apply.

Stage Four: Scramble to negotiate bilateral arrangements from a weaker position.

Stage Five: Achieve worse terms than before, if any terms at all.

The steel sector joins fishing, financial services, agriculture, and manufacturing in learning this lesson. Each industry was told Brexit would bring opportunity. Each has found barriers where there were none and opportunities that remain theoretical.

The government talks of “pushing for carve-outs.” But Brussels has no incentive to provide them. The EU is protecting its 300,000 direct steel jobs and 2 million indirect jobs from Chinese overcapacity and Trump’s tariffs. Britain’s 1.9 million tonnes of exports represent 6% of the reduced quota system. Why would the EU prioritize a country that chose to leave over members that remained?

The Reality Check

Strip away the diplomatic language and three facts remain:

First: Britain depends on European steel buyers but gave up the institutional mechanisms that guaranteed market access.

Second: The government had years to prepare for this scenario and appears to have done nothing effective.

Third: British steelworkers will now pay the price for political choices they had no power to prevent.

Industry minister Chris McDonald, a former steel executive, held urgent meetings with UK steelmakers on Wednesday. They told him the UK must secure country-specific exemptions and quickly replace expiring British safeguards to prevent diverted steel flooding the domestic market.

These are reasonable requests. They are also requests that should have been negotiated years ago, from within the institutional frameworks Britain abandoned. Asking for them now, after the tariffs are announced, reveals the government’s position: supplicant, not partner.

The chancellor promised at Labour’s conference to direct government steel spending to British steelworks. This sounds decisive. It addresses roughly half of Britain’s steel consumption, since imports are double domestic production. It does nothing for the 78% of British steel production that depends on European buyers who must now pay 50% more.

The Institutional Failure

The deeper problem is not the EU tariff itself. Brussels faces the same Chinese overcapacity and Trump tariffs that threaten all Western steel producers. The EU steel industry has not been modernized in 40 years. Capacity utilization has dropped from 80% in 2008 to 65% in 2024. European steelmakers are fighting for survival.

The failure is Britain’s. Specifically:

No Strategic Preparation: The Trump tariffs came in June 2025. EU safeguards were expiring in June 2026. The direction was clear. Where was the UK’s plan?

No Negotiated Protection: EEA members secured automatic exemptions because they remained integrated into single market structures. Britain chose to leave and negotiated nothing equivalent.

No Alternative Markets: The government speaks vaguely of “looking elsewhere” for buyers. Where? The US has 25% tariffs. Global markets are flooded with Chinese steel. The top five UK export destinations are all in the EU.

No Domestic Resilience: Britain imports twice the steel it makes. This is not energy independence or industrial security. This is structural vulnerability.

The pattern extends beyond steel. Britain keeps discovering that sovereignty without capacity is just isolation with better branding. The power to make independent decisions means little when those decisions consistently produce worse outcomes than the arrangements they replaced.

The Bigger Picture

This is what decline looks like in practice. Not dramatic collapse, but steady erosion of industrial capacity, market access, and economic options.

Britain had guaranteed access to its largest export market for steel. It gave that up. It was told this would bring new opportunities and better deals. Those have not materialized. Now it faces tariffs designed to protect an integrated market it chose to leave, while watching EEA members maintain the access Britain abandoned.

The steel sector directly employs tens of thousands of people in Wales, Scunthorpe, and Scotland. Indirectly, it supports supply chains, communities, and regional economies already hollowed out by decades of industrial decline. These workers were promised Brexit would protect British industry. Instead, it has exposed that industry to competitive disadvantages their continental counterparts do not face.

The government will negotiate. It will push for quotas and exemptions. It may secure some concessions. But it will do so as a supplicant asking for special treatment, not a member exercising institutional rights. The difference matters. Members have legal guarantees. Supplicants have whatever Brussels chooses to offer.

TheDecliner has documented this pattern across sector after sector: promises of sovereignty delivering isolation, claims of opportunity producing barriers, assertions of strength revealing weakness. The steel tariffs are not an anomaly. They are the system working exactly as it was designed to work after Britain removed itself from it.

The question is no longer whether Brexit has damaged British industry. The evidence answers that. The question is how much more damage British workers must absorb before the political class acknowledges what the data has shown for years: Britain gambled its industrial future on ideological promises and lost.

The steel sits unsold. The furnaces face closure. The workers watch their industry become uncompetitive through no fault of their own. And the politicians who promised Brexit would protect British jobs now scramble to explain why the largest market for British steel has just become prohibitively expensive to access.

This is Britain’s industrial policy in 2025: begging for exemptions from barriers it created itself.

Commentary based on ‘Existential threat’: what do EU’s 50% steel tariffs mean for UK industry? by Jasper Jolly, Lisa O’Carroll on The Guardian.