Twenty Years of Warnings, Zero Years of Action: How Britain's Housing Crisis Became a Climate Catastrophe

The heatwaves are here to stay, and so are the consequences of our inaction.

While ministers debate subsidizing air conditioning in 2025, the UK housing stock remains fundamentally unfit for the climate conditions we've already experienced. The 40°C temperatures that struck in 2022 weren't a distant possibility requiring decades of preparation—they were the arrival of a predicted reality that successive governments chose to ignore.

Commentary Based On

The Guardian

Overheated homes: Why UK housing is dangerously unprepared for impact of climate crisis

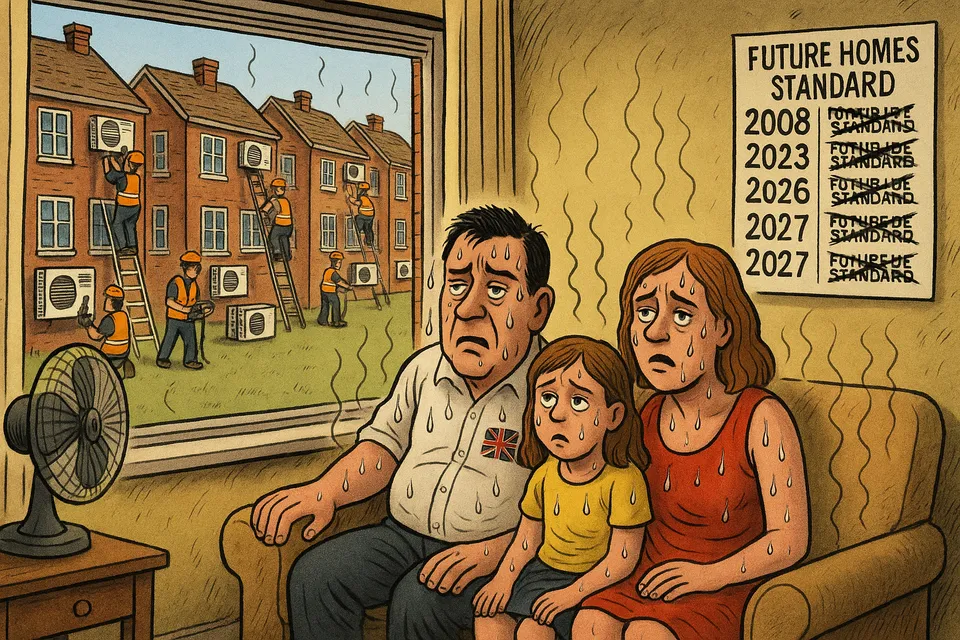

The Future Homes Standard, now promised for 2027, was first conceived in 2008. That’s nineteen years from initial planning to implementation for regulations addressing a crisis that climate scientists have been warning about since the 1990s. This isn’t policy-making; it’s institutional paralysis masquerading as governance.

The Facts That Matter

The Timeline of Failure:

- 2008: Labour introduces plans for climate-adapted homes

- 2015: Conservatives scrap the plans entirely

- 2022: Part O building regulations finally introduced—only for new homes

- 2022: UK experiences 40°C temperatures, thousands of excess deaths

- 2025: Government “considering” air conditioning subsidies

- 2027: Future Homes Standard might finally take effect

The Current Reality:

- 28°C internal temperatures will become normal in London and the Southeast

- The Met Office predicts 40°C summers will repeat within 12 years

- Only homes built after June 2022 have any overheating protections

- No retrofit plans exist for Britain’s 29 million existing homes

- The draft Future Homes Standard still fails to address overheating adequately

The Energy Contradiction: The government simultaneously claims to pursue net zero while considering subsidizing air conditioning—one of the most energy-intensive cooling methods available. The UN has already warned that global air conditioning demand is overwhelming renewable energy gains. Britain’s solution to decades of building inadequate homes? Add more energy demand to an already strained grid.

Institutional Decay in Three Acts

Act One: The Knowledge Gap That Wasn’t

The Climate Change Committee has “repeatedly highlighted” the lack of urgent adaptation effort. This phrase conceals a more damaging truth: every warning was received, acknowledged, and systematically ignored. This wasn’t ignorance—it was informed negligence.

When Simon McWhirter of the UK Green Building Council states we’re “facing climate brutality,” he’s describing conditions that have been predictable and predicted for over two decades. The surprise isn’t the heat; it’s that anyone expected different outcomes from the same failed institutions.

Act Two: The Industry Capture

The Home Builders Federation claims new homes stay “cooler in summer” due to insulation requirements. Yet these are the same homes that Part O regulations had to be introduced to protect from overheating—regulations that only came into force in 2022. The industry spent fourteen years building homes they knew would overheat, protected by governments that refused to regulate them.

Steve Turner’s assertion that insulation alone solves overheating contradicts the government’s own admission that current standards are inadequate. This is the voice of an industry that has successfully resisted meaningful regulation for two decades, now claiming their minimal compliance represents excellence.

Act Three: The Political Theatre

Labour promises 1.5 million new homes this parliament. Even if achieved—and recent history suggests it won’t be—these will represent a fraction of housing stock. Meanwhile, there are “no substantial plans” to retrofit existing homes against overheating. Translation: 95% of British homes will remain dangerously inadequate for predictable climate conditions.

The government spokesperson’s response is a masterclass in bureaucratic deflection: “We know the importance of keeping homes cool.” They’ve known for twenty years. The question isn’t knowledge—it’s why that knowledge never translates into action.

The Pattern of Perpetual Deferral

This housing crisis exemplifies Britain’s governing pathology: endless consultation, perpetual delay, and eventual delivery of solutions designed for yesterday’s problems. The Future Homes Standard addresses the climate of 2010, not 2030. By 2027, when it might take effect, it will already be obsolete.

Consider the sequence:

- Problem identified (1990s-2000s)

- Solution proposed (2008)

- Solution cancelled for political reasons (2015)

- Crisis arrives (2022)

- Panic response proposed (air conditioning subsidies, 2025)

- Original solution maybe implemented (2027)

- Solution already inadequate upon arrival

This isn’t governance; it’s a cargo cult of policy-making where the appearance of action substitutes for results.

The Real Cost of Institutional Failure

When 28°C becomes normal inside British homes, the consequences won’t be equally distributed. The wealthy will install cooling systems, move to better-adapted properties, or simply leave during heat waves. The poor, elderly, and vulnerable will suffer in overheated boxes that the state assured them were “built to exceptional standards.”

The 3,000 excess deaths during the 2022 heatwave weren’t natural disasters—they were political choices crystallized into mortality statistics. Every death represents someone failed by institutions that had decades to prepare and chose not to.

The energy costs of retrofitting air conditioning across millions of homes will dwarf what proper building standards would have cost. The health service will bear the burden of heat-related illness. Productivity will plummet during increasingly common heat waves. This isn’t just environmental failure—it’s economic sabotage through negligence.

The Accountability Vacuum

Who exactly is responsible for two decades of inaction? The politicians who cancelled programs? The civil servants who slow-walked implementation? The builders who lobbied against regulation? The answer, in Britain’s accountability-free governance model, is no one.

Labour blames the Conservatives for cancelling their 2008 plans. Conservatives blame Labour for not acting sooner. The Home Builders Federation insists they follow whatever regulations exist. The Climate Change Committee issues warnings but has no power. Citizens suffer the consequences of decisions made in rooms they’ll never enter by people they’ll never meet.

What Competent Governance Would Look Like

A functioning state would have acted on climate science in the 2000s, implemented building standards by 2010, and begun systematic retrofitting by 2015. By 2025, the housing stock would be adapted, energy-efficient, and resilient. This isn’t fantasy—it’s what comparable European nations have achieved.

Instead, Britain offers its citizens a choice between overheating in summer and freezing in winter, with both outcomes increasingly expensive and dangerous. The Future Homes Standard, when it finally arrives, will be another monument to institutional inadequacy—too little, too late, and already obsolete.

The Bigger Picture

Britain’s housing crisis isn’t separate from its broader decline—it’s symptomatic of it. A country that cannot execute basic infrastructure adaptation after decades of warning is a country whose governing institutions have fundamentally failed.

The overheated homes of 2030s Britain won’t just be uncomfortable—they’ll be physical monuments to institutional decay. Every sweltering bedroom, every heat-stressed hospital ward, every air conditioning unit desperately retrofitted to an unsuitable building will testify to the same truth: the British state no longer functions at the level required for basic civilizational maintenance.

When future historians document Britain’s decline, they won’t need to examine complex financial instruments or constitutional arrangements. They’ll simply note that a nation with two decades of warning couldn’t manage to build homes suitable for predictable weather. The rest will be commentary.

Commentary based on Overheated homes: Why UK housing is dangerously unprepared for impact of climate crisis by Fiona Harvey on The Guardian.