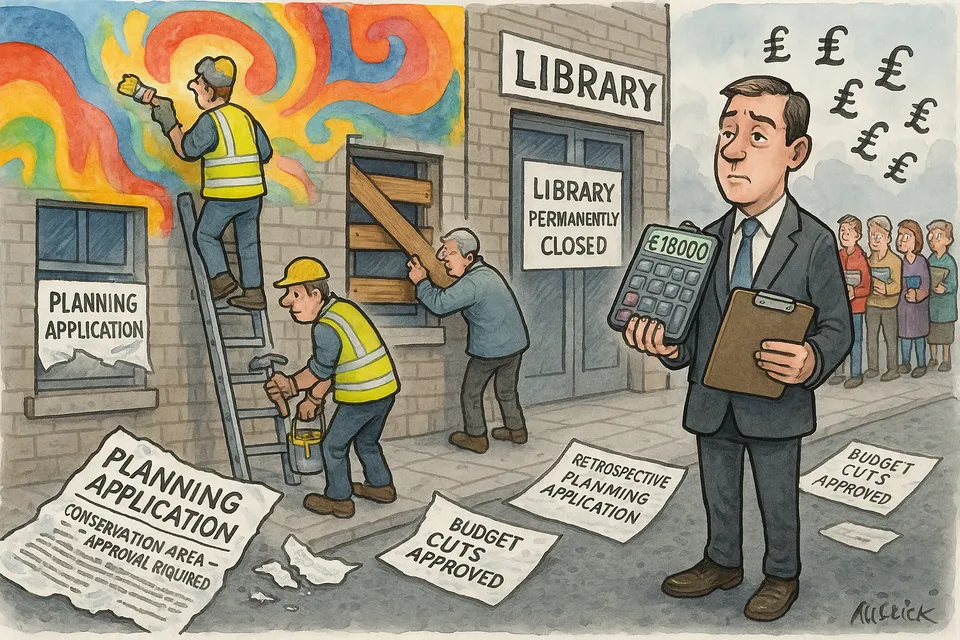

When The Rule-Makers Break The Rules: Enfield's £18,000 Lesson in Local Government Dysfunction

Council spends £18,000 on mural while closing libraries

Enfield's £18,000 mural debacle highlights a troubling trend in local governance: the prioritization of aesthetics over essential services. As councils grapple with budget constraints, the choices they make reveal a disturbing disconnect from the needs of their communities.

Commentary Based On

The Telegraph

Labour-run Enfield council painted £18k ‘eyesore’ mural without permission

The Facts: Enfield council spent £18,000 of public money on a mural without obtaining required planning permission, while simultaneously closing seven libraries to save money. The council now seeks retrospective permission for work already completed on a building in a conservation area.

The Reality: This is not about art or heritage. This is about how local government actually operates in modern Britain.

What Actually Happened

Enfield council commissioned artist Albert Agwa to paint a multicoloured mural on the side of Enfield Town library at a cost of £18,000. The work was completed without planning permission despite the library sitting in a conservation area where such permissions are mandatory. The council has since filed for retrospective planning permission.

The mural was painted while the council prepares to close seven libraries permanently, cutting £630,000 from annual spending and selling the properties. The timing is not coincidental. It is institutional.

Council officials claim the £18,000 came from Community Infrastructure Levy funds, money paid by developers that is supposedly ring-fenced for community improvements. They frame this as financially responsible because these funds cannot be used for other council services.

The facts suggest otherwise.

The Pattern of Institutional Failure

Rule-breaking by rule-makers: Conservation area regulations exist to protect local heritage. These same regulations bind every resident and property owner in Enfield Town. Yet the council responsible for enforcing these rules simply ignored them when inconvenient.

No council officer was disciplined. No process was reviewed. The response was administrative: file the paperwork afterwards and hope nobody notices the sequence of events.

Priority inversion: While cutting library services that residents actually use, the council found £18,000 for a decorative project that required no public consultation and serves no measurable community need. The symbolism is deliberate: visual gestures matter more than functional services.

Accountability gaps: The council’s explanation that CIL funds are ring-fenced reveals how public sector accounting operates in practice. Money is categorised in ways that allow officials to claim their hands are tied while making choices that serve institutional interests over public ones.

The question is not whether the ring-fencing rules are technically correct. The question is who designed a system where councils can spend thousands on murals while claiming they cannot afford libraries.

What The Evidence Shows

Enfield’s library closures will save £630,000 annually. The mural cost £18,000. In purely financial terms, the mural represents roughly 10 days of library funding across seven sites.

But the calculation misses the institutional reality. Library services require ongoing staff costs, maintenance, and operational complexity. Murals require a one-time payment to a contractor with no ongoing accountability or performance measures.

From an institutional perspective, the mural is a simpler transaction. Pay the artist. File the paperwork. Move on. Libraries involve staff management, public complaints, performance monitoring, and visible service failures when things go wrong.

The council chose the easier option, not the more important one.

The Conservation Area Question

Planning permission exists for a reason. Conservation areas have special protections because elected officials and planning experts determined these locations merit preservation. The system assumes that those responsible for enforcement will follow the same rules they impose on others.

Enfield council’s approach reveals how institutional accountability actually works. Rules apply to private individuals and businesses who face penalties for non-compliance. Rules become guidelines for institutions with the power to grant themselves retrospective permission.

The council’s planning documents acknowledge the library’s brickwork “was not originally intended for murals and may be vulnerable to moisture penetration, surface cracking and UV exposure.” They proceeded anyway.

This is not incompetence. This is how the system works when institutions regulate themselves.

The Broader Context

Enfield council is not uniquely dysfunctional. Similar patterns emerge across local government: symbolic spending continues while core services are cut, regulations are enforced selectively, and public accountability operates differently for institutions than for individuals.

The council’s defence focuses on funding technicalities rather than priority decisions. Officials claim they followed consultation processes and considered community views. The evidence suggests otherwise: the work was completed before planning permission was sought, indicating the consultation was performative.

This is institutional behaviour optimised for avoiding responsibility rather than delivering results.

What This Really Reveals

The mural controversy exposes how local government decision-making actually functions. Officials operate within systems designed to minimise accountability while maximising bureaucratic flexibility. Rules become suggestions when they conflict with institutional preferences.

The £18,000 figure is less important than the process that produced it. A council facing budget constraints found money for discretionary spending while cutting essential services, ignored its own regulations, and defended the decisions with technical justifications that miss the fundamental questions.

This is not about political affiliation. Conservative councils exhibit identical behaviour patterns. The issue is institutional, not partisan.

The Reality Check

Enfield residents now have a £18,000 mural on a building that may suffer moisture damage, in a conservation area where the work should not have been approved without prior permission, paid for while their libraries are being closed.

The council responsible for this sequence of decisions continues to operate with the same processes, personnel, and accountability structures that produced these outcomes. Nothing has changed except the paperwork trail.

This is how institutional decline manifests in practice: not through dramatic failures, but through routine decisions that prioritise bureaucratic convenience over public service, symbolic gestures over functional delivery, and institutional interests over community needs.

The mural itself is irrelevant. The system that produced it remains intact.

Commentary based on Labour-run Enfield council painted £18k ‘eyesore’ mural without permission by Telegraph Reporters on The Telegraph.