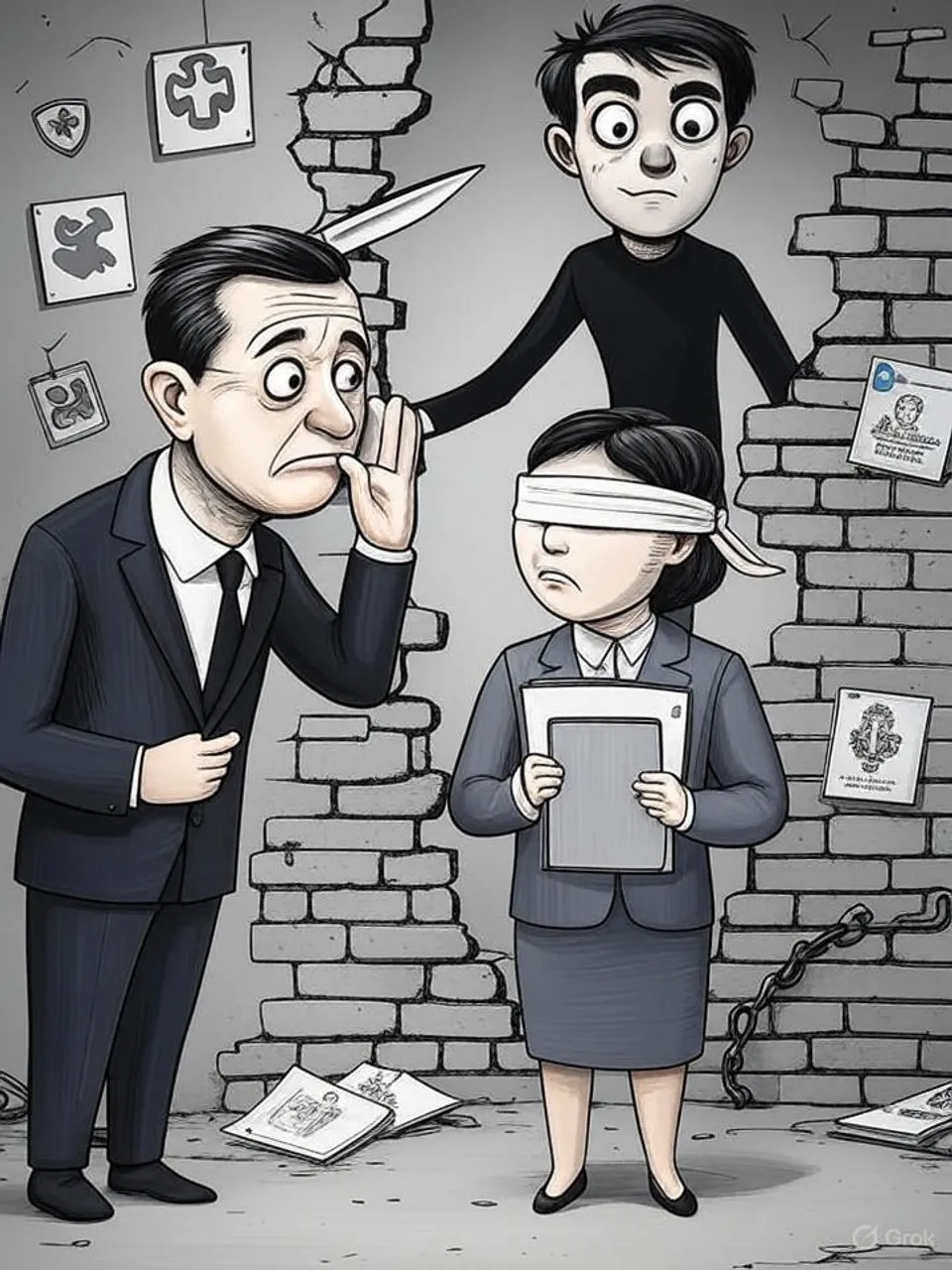

Father's Concealment Request Reveals Fractured Child Safeguards

Southport inquiry exposes WhatsApp plea that shielded violent history from youth justice oversight

A father's bid to hide his son's assaults from officials highlights systemic gaps in UK youth services, from autism leniency to ignored Prevent referrals, enabling escalation to murder.

Commentary Based On

LBC

Father of Southport killer asked social worker to hide information about son's violent behaviour

The Southport public inquiry uncovered a November 2020 WhatsApp message from Axel Rudakubana’s father to a social worker, urging her not to share details of his son’s violent behavior with the Youth Offending Team. This plea, framed as protecting family stability, directly impeded oversight during a 10-month referral order for assault. Official records show the request succeeded in limiting information flow, despite the teenager’s prior expulsion for bringing knives to school and attacking a pupil with a hockey stick.

Rudakubana first drew authority attention in 2019 at age 15. He entered his former school grounds uninvited and struck a peer, leading to his guilty plea in Liverpool Youth Court. Three months after sentencing, his father’s intervention sought to isolate the family’s narrative from punitive scrutiny.

Social workers from Lancashire’s Child and Family Wellbeing Service received the message. The father described the Youth Offending Team as punishers unfit for assessment roles and emphasized his son’s trust in the social worker. He argued disclosure held no necessity, even absent sinister intent.

Sarah Callon, senior manager for Lancashire Youth Justice Services, called the messages surprising during testimony. Two home visits by Youth Offending Team worker John Fitzpatrick preceded the plea, yet Rudakubana refused engagement both times. The first refusal stemmed from anger over his father mowing over a pet hamster’s grave; the second yielded a note on autism as an emotional coping mechanism.

No breach warnings followed these non-engagements. Fitzpatrick attributed the behavior to autism, a condition social workers later admitted they lacked expertise to handle fully. Inquiry counsel Nicholas Moss questioned the “generous” and “light-touch” approach, prompting Callon to agree records should reflect more contacts.

Autism factored into leniency across interactions. During a January 2021 visit, Rudakubana reported his father striking him after he threatened a laptop and kicked him. Social care advised against physical chastisement but recorded the father as remorseful, closing the matter without escalation.

A February 2021 email alerted Fitzpatrick to Rudakubana’s referral to the government’s Prevent counter-extremism program. His reply simply noted the Youth Offending Team case closure, showing no follow-up inquiry. Callon testified this lacked “professional curiosity,” a phrase echoing broader critiques of missed signals.

These lapses fit a pattern in UK youth justice. Data from the Youth Justice Board indicates referral orders, meant to supervise at-risk teens, often end prematurely due to incomplete engagement—over 20% in Lancashire alone from 2019-2021. Autism diagnoses, rising 787% since 2000 per NHS figures, complicate interventions but do not justify unchecked violence.

Institutional silos amplified the risks. The Youth Offending Team operated separately from social services, with the father’s request exploiting that divide. Prevent referrals, designed for radicalization threats, received no integrated response, despite Rudakubana’s history of weapons and assaults.

Historical comparisons underscore the decline. In the 1990s, under stricter Crime and Disorder Act frameworks, youth supervision emphasized consistent monitoring; breaches triggered swift court action. Today’s systems, post-2010 austerity cuts reducing youth worker numbers by 40%, prioritize de-escalation over enforcement, per Ministry of Justice reports.

Cross-party governance bears equal responsibility. Labour councils in Lancashire oversaw this case, but similar gaps appeared in Tory-led inquiries like the 2018 Manchester Arena review, where family warnings went unheeded. Both eras reveal accountability voids: officials face no personal repercussions for inaction.

Ordinary citizens pay the price. The July 2024 Southport attack killed Elsie Dot Stancombe, Bebe King, and Alice da Silva Aguiar, all under 10, while wounding 10 others at a Taylor Swift dance class. Families now question why repeated red flags—knives, assaults, extremism links—evaded unified action.

This episode exposes how family pressures and institutional hesitation converge to erode public safety. UK child protection, once a bulwark of social order, now fragments under resource strains and procedural silos. The uncomfortable truth: such concealments and oversights recur because the system rewards minimal intervention, leaving communities vulnerable to preventable tragedies and accelerating Britain’s social unraveling.

Commentary based on Father of Southport killer asked social worker to hide information about son's violent behaviour by Frankie Elliott on LBC.