When Central Banks Stop Being Central: The Bank of England's Thursday Capitulation

The Bank of England's Independence Is Dead – Markets Know It, Even If Politicians Don't

Britain's central bank has lost its credibility, and the markets are reacting accordingly. The recent interest rate cut is a clear signal that the Bank of England is no longer the independent institution it once was.

Commentary Based On

When the Facts Change

The Bank of England was wrong to cut rates – government borrowing costs since have risen even more

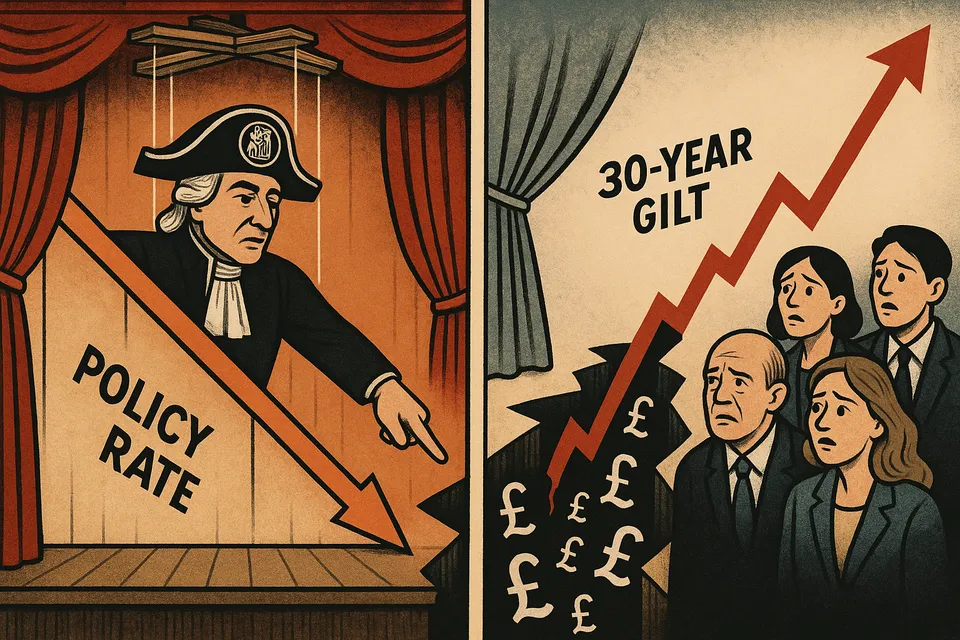

Last Thursday, the Bank of England cut interest rates from 4.25% to 4%, and the government immediately claimed credit for the decision. In the financial markets, where real money changes hands rather than press releases, the response was telling: the 30-year UK government bond yield moved in the opposite direction, widening what Liam Halligan identifies as a dangerous “rate-splitting” gap between official policy rates and actual borrowing costs.

This divergence reveals something more profound than a technical anomaly. When markets refuse to follow central bank signals, they’re pricing in institutional failure. The Bank of England, once a model of independent monetary policy copied worldwide, has become another casualty of Britain’s institutional decay.

The Context

The Monetary Policy Committee’s decision came after months of economic deterioration. GDP contracted in both April and May, the most recent data available when the MPC met. Inflation continues to exceed the 2% target that supposedly guides all Bank decisions. Government borrowing costs have been rising despite five consecutive rate cuts since August, when the benchmark rate stood at 5.25%.

Against this backdrop, the committee split 5-4 on the decision. Four members understood that cutting rates into persistent inflation while the economy shows structural weakness violates basic monetary policy principles. Five members voted to cut anyway. In that narrow margin lies the story of an institution abandoning its mandate for political convenience.

The government’s rush to claim credit exposed what market participants already suspected: the Bank of England’s independence has become performative rather than substantive. Chancellor Rachel Reeves’s immediate celebration of the cut as validation of government policy destroyed any remaining pretense of separation between Threadneedle Street and Westminster.

The Evidence

Market behavior provides the clearest evidence of lost credibility. Since August, each of the five rate cuts has been accompanied by the same pattern: policy rates fall, but actual borrowing costs for government and businesses either rise or remain elevated. This “rate-splitting” phenomenon, as Halligan describes it, represents international investors demanding higher returns to compensate for UK institutional risk.

The data tells a stark story. While the MPC has reduced rates by 125 basis points since their peak, 30-year gilt yields have barely budged, and mortgage rates for ordinary Britons remain punishingly high. Banks and building societies, watching the same institutional decay that international investors see, refuse to pass on the supposed benefits of lower policy rates.

Consider the historical context. When the Bank gained independence in 1997, the spread between policy rates and market rates narrowed significantly, reflecting increased confidence in UK monetary policy. That hard-won credibility, built over decades, is now evaporating in real time. Each basis point of widening spread represents another degree of lost faith in British institutions.

The Pattern

This surrender follows a familiar template across declining British institutions. First comes political pressure dressed as economic necessity. Then arrives the rationalization that “exceptional circumstances” require flexibility with established principles. Finally, the institution continues using the vocabulary of independence while functioning as an extension of government policy.

We witnessed this pattern at the Office for Budget Responsibility, whose forecasts now mysteriously align with whatever the government needs them to show. The same degradation infected the civil service during COVID, when “following the science” meant following political imperatives. Public Health England, the Electoral Commission, even the BBC have all traveled this same path from independence to institutional capture.

The four MPC members who voted against the cut deserve recognition for maintaining professional standards under pressure. They recognized that cutting rates when inflation remains elevated, government spending lacks control, and currency stability faces threats amounts to monetary malpractice. Their minority status on the committee reveals how thoroughly political considerations now dominate what should be technical decisions.

The Reality Check

For ordinary Britons, this institutional failure translates into immediate economic consequences. Despite the Bank’s “rate cut,” mortgage holders face unchanged or rising borrowing costs. First-time buyers watch affordability deteriorate further as lenders price in currency and inflation risks that the Bank refuses to acknowledge. Savers see their purchasing power erode as inflation exceeds the returns available from deposits.

The government’s borrowing costs tell an even grimmer story. International investors now demand risk premiums typically associated with emerging markets rather than developed economies. Every gilt auction becomes more expensive, with taxpayers ultimately bearing the cost through either higher taxes or degraded public services. The market has essentially reclassified the UK from a stable developed economy to something altogether less reliable.

Business investment, already anemic by international standards, faces additional headwinds as companies struggle to reconcile official interest rates with actual borrowing costs. Why would any rational business make long-term commitments in an economy where the central bank has abandoned its primary function of maintaining monetary stability?

The Bigger Picture

Britain once exported the concept of independent central banking to the world. The Bank of England’s model influenced institutional design from Frankfurt to Wellington. Now we import the characteristics of economically unstable nations: political interference in monetary policy, short-term thinking trumping long-term stability, and technical expertise subordinated to electoral calculations.

The transformation from institutional exemplar to cautionary tale hasn’t occurred through revolution or crisis. Instead, standards have been quietly abandoned, one decision at a time, each compromise justified as pragmatic or necessary. The MPC’s Thursday decision represents another milestone in this descent, notable not for its drama but for its banality.

What makes this particularly damaging is the timing. Global economic conditions remain fragile, with inflation proving more persistent than predicted and geopolitical tensions threatening supply chains. Britain needs credible, independent monetary policy more than ever. Instead, we have a central bank that functions as the Treasury’s monetary department, making decisions based on political cycles rather than economic cycles.

The narrow 5-4 split within the MPC offers a glimmer of recognition that something has gone badly wrong. Nearly half the committee understands that capitulating to political pressure while inflation remains uncontrolled represents a dereliction of duty. Yet in modern Britain, being right counts for nothing if those willing to be wrong for career advancement outnumber you.

Market participants have rendered their verdict through the growing rate-splitting gap. They see a country where institutions built over centuries can be compromised over parliamentary terms. They price accordingly, demanding compensation for lending to a nation whose commitment to sound money has become negotiable.

The Bank of England’s Thursday capitulation wasn’t dramatic. No resignation letters were published, no constitutional crisis declared. Just another committee meeting where political expedience defeated economic principle by a single vote. In the annals of institutional decline, the most consequential failures often arrive disguised as reasonable compromises. Thursday’s rate cut was precisely such a moment, when the Bank of England ceased being truly central to Britain’s monetary system and became merely another department of a government that has run out of both ideas and credibility.

Commentary based on The Bank of England was wrong to cut rates – government borrowing costs since have risen even more by Liam Halligan on When the Facts Change.