Britain's Pharmaceutical Exodus: When Even Big Pharma Won't Take Your Money

How Bureaucratic Short-Sightedness is Driving Life Sciences Out of the UK

When the CEO of a $700 billion pharmaceutical giant publicly declares that the UK is "probably the worst country in Europe" for drug prices, it's a stark warning sign. Eli Lilly's Dave Ricks isn't just lamenting high taxes; he's signaling a broader institutional failure that's driving investment and innovation out of Britain. This analysis explores how bureaucratic short-termism and irrational pricing schemes are dismantling what was once a global leader in life sciences.

Commentary Based On

The Independent

Mounjaro manufacturer blasts UK as ‘worst country in Europe’ for drug prices

The CEO of a $700 billion pharmaceutical giant just delivered a diagnosis Britain didn’t want to hear: the UK has become “probably the worst country in Europe” for medicine pricing. Dave Ricks of Eli Lilly isn’t some disgruntled startup founder—he runs the company behind Mounjaro, one of the most sought-after drugs on the planet. When someone in his position publicly warns that Britain “won’t see many new medicines” or “much investment,” it’s not negotiation tactics. It’s a corporate death notice.

The Evidence

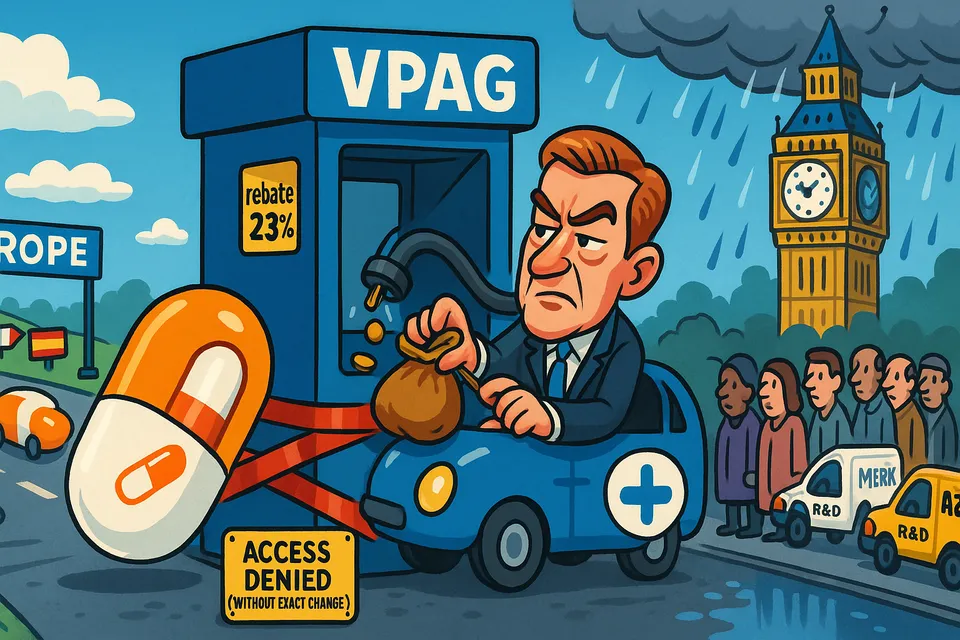

The pharmaceutical retreat is accelerating across multiple fronts. Merck has abandoned its planned £740 million research hub. AstraZeneca—a British company—has frozen a £200 million Cambridge investment. These aren’t minor adjustments or temporary pauses. These are strategic withdrawals from what was once considered Europe’s premier life sciences market.

The mechanism driving this exodus is the Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing, Access and Growth (VPAG)—a bureaucratic contraption that forces pharmaceutical companies to pay back portions of their UK sales to the NHS. Ricks calls it a scheme that charges companies “for their own success.” The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry confirmed in August that negotiations to reform it had failed entirely.

The absurdity reaches peak levels with Mounjaro itself. Eli Lilly had to raise UK prices by 170% for private buyers because the artificially low NHS prices had created a bizarre arbitrage opportunity. French patients were literally taking trains to Britain to buy cheaper weight-loss drugs and return home. Britain had somehow managed to become the pharmaceutical equivalent of a duty-free shop—unsustainable pricing that benefits foreign consumers while destroying domestic investment incentives.

Critical Analysis

This isn’t just about drug prices or corporate profits. This is about Britain systematically dismantling its own competitive advantages through bureaucratic short-termism. The life sciences sector generates £100 billion annually and supports 300,000 jobs. Yet the government is treating it like a cash cow to be milked rather than an innovative industry to be cultivated.

The VPAG scheme exemplifies everything wrong with modern British governance: a “voluntary” scheme that’s actually mandatory, a “growth” initiative that punishes success, and an “access” program that’s now threatening to reduce access to new medicines entirely. It’s institutional doublespeak wrapped in acronyms.

Consider the perversity: Britain needs pharmaceutical innovation more than ever. An aging population, rising chronic disease rates, NHS waiting lists at record highs. Yet the pricing structure actively repels the very companies developing solutions to these problems. It’s like turning away firefighters during a blaze because you object to their hourly rates.

The Pattern

This pharmaceutical exodus follows a familiar template of British institutional failure. First, create a complex bureaucratic scheme to solve a simple problem. Second, ignore industry warnings about unintended consequences. Third, watch as global companies quietly redirect investment elsewhere. Fourth, issue press releases about “commitment to innovation” while the sector hollows out.

The government spokesperson’s response is textbook decline management: acknowledge there’s “more work to do,” announce various funds and initiatives with impressive-sounding numbers, and hope nobody notices that the actual businesses are leaving. They’re investing “up to £600 million” in data services while losing billions in actual pharmaceutical investment.

What makes this particularly damaging is timing. The global pharmaceutical industry is experiencing unprecedented growth. Weight-loss drugs alone are creating a multi-hundred-billion dollar market. Gene therapies, AI-driven drug discovery, precision medicine—revolutionary developments are accelerating. And Britain is managing to price itself out of participation just as the real breakthroughs begin.

The Reality Check

When pharmaceutical executives publicly blast your country’s pricing structure, they’re not opening negotiations—they’re explaining why they’re leaving. Ricks isn’t asking for minor adjustments to VPAG. He wants it gone entirely. And given the choice between accepting UK prices or simply not launching new drugs here, companies are increasingly choosing the latter.

The French train story is particularly revealing. It shows Britain has achieved the worst of all worlds: prices so low that they create international arbitrage opportunities, yet still too high for many NHS patients to access these drugs. The system fails both companies and patients while creating absurd inefficiencies that benefit neither.

Meanwhile, other European countries are capturing the investment Britain is losing. They’ve figured out that sustainable pricing that allows for innovation is better than short-term savings that drive companies away. Britain, apparently, has not.

The Bigger Picture

The pharmaceutical industry’s verdict on Britain represents more than lost investment or delayed drug access. It’s a leading indicator of broader institutional decay. When one of the world’s most profitable industries—one that prints money almost regardless of economic conditions—declares your country uninvestable, you’ve achieved a special kind of failure.

This is what managed decline looks like in practice: not dramatic collapse but gradual withdrawal. Companies don’t announce they’re abandoning Britain; they simply stop launching new products here. Investment doesn’t halt overnight; it quietly redirects to friendlier markets. Innovation doesn’t disappear; it just happens somewhere else.

The 300,000 jobs in life sciences won’t vanish immediately. They’ll erode slowly as research moves to Boston, manufacturing shifts to Ireland, and new facilities get built in Singapore instead of Cambridge. By the time the full impact becomes undeniable, the industry’s center of gravity will have shifted permanently elsewhere.

Britain once pioneered modern pharmaceuticals. From penicillin to IVF to DNA sequencing, British science led the world. Now we’re haggling over drug prices while the future of medicine develops elsewhere. The country that gave the world antibiotics can’t figure out how to price obesity drugs without driving away their manufacturers.

This is institutional decline in its purest form: taking a world-leading sector and regulating it into retreat through a combination of bureaucratic complexity, short-term thinking, and an inability to understand basic economic incentives. The Decliner’s prediction: within five years, British patients will be traveling to Europe for advanced treatments the NHS can’t access. The trains from Paris will be running in the opposite direction.

Commentary based on Mounjaro manufacturer blasts UK as ‘worst country in Europe’ for drug prices by Karl Matchett on The Independent.