Fly-Tippers Turn Oxfordshire Floodplain into Toxic Heap

A 150m waste mountain threatens the River Cherwell as agencies cite budget shortfalls

Illegal dumping near Kidlington exposes enforcement paralysis, with cleanup costs overwhelming local budgets and risks mounting to waterways. Systemic under-prioritization allows organized crime to poison Britain's rural landscapes unchecked.

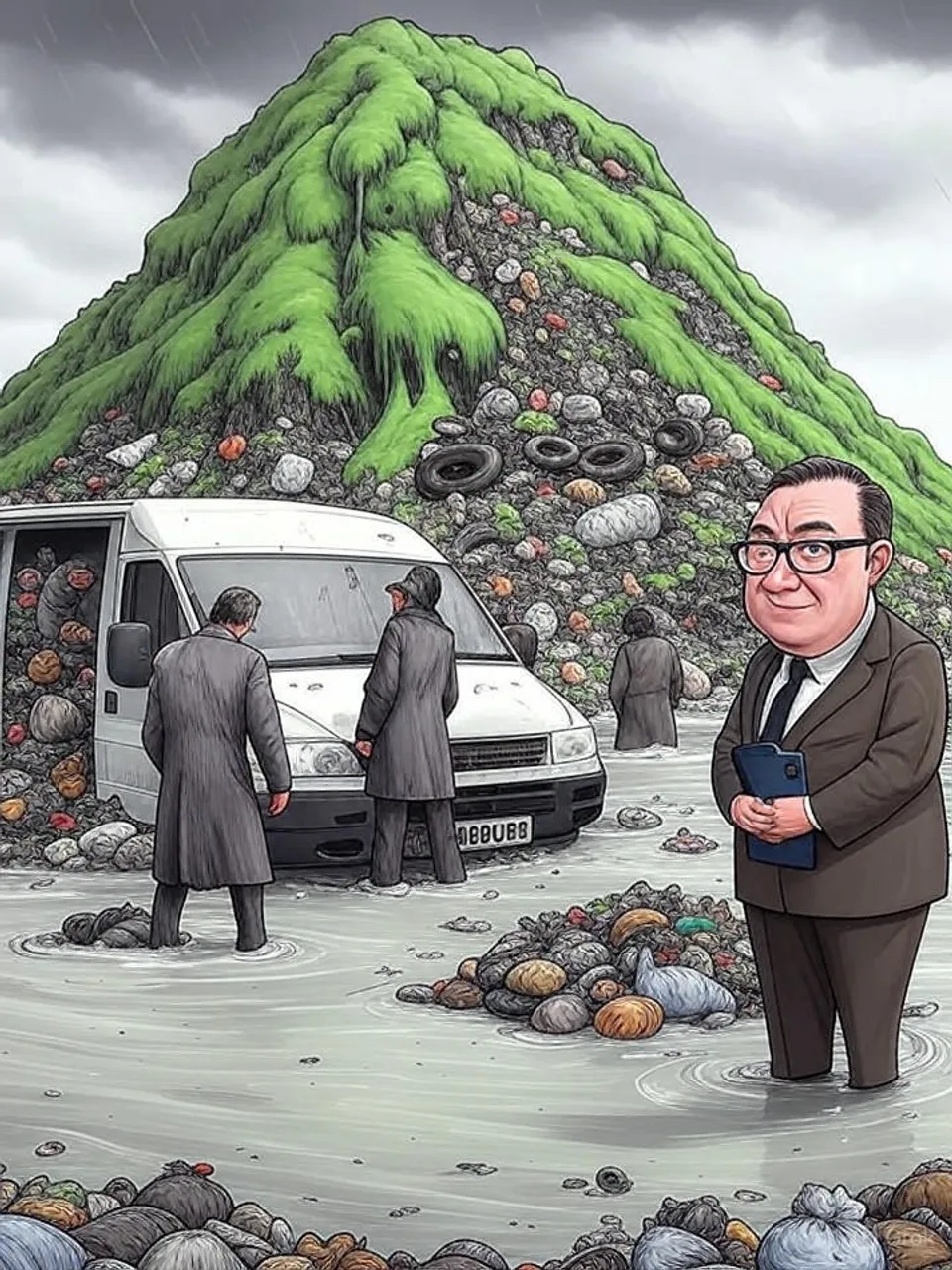

A 150-meter-long mound of shredded waste, rising six meters high, now dominates a field between the A34 and River Cherwell near Kidlington. Local MP Calum Miller told Parliament the cleanup would exceed Cherwell District Council’s entire annual budget, yet the Environment Agency insists on the polluter pays principle without immediate intervention. This standoff leaves hundreds of tonnes of illegal rubbish exposed to rising river levels and potential fires.

The dump appeared about a month ago, courtesy of an organized crime group, according to Friends of the Thames charity. Shredded plastics mixed with earth obscure the contents, but the scale suggests industrial-level dumping. Drone footage reveals the pile stretching like a debris river through trees, just five meters from the riverbank at its closest point.

Cherwell District Council faces a financial impasse. Removal estimates surpass their yearly budget, forcing reliance on national agencies ill-equipped to act swiftly. Taxpayers in the area, already funding local services, now shoulder indirect costs through polluted waterways and devalued land.

The Environment Agency issued a restriction order to block further access, but enforcement remains limited. Officials cite resource constraints and prioritize only imminent threats to life under their mandate. Investigations proceed, but the agency appeals for public tips rather than deploying teams for clearance.

Mary Creagh, the environment minister, blamed an inherited “failing waste industry” for the fly-tipping epidemic during parliamentary debate. She highlighted the agency’s role in pursuing culprits, yet admitted the problem’s scale. This echoes a House of Lords report from October, which labeled waste crime efforts “critically under-prioritised” amid growing sophistication.

Enforcement Gaps Widen

Waste crime has evolved into organized operations, evading detection through shredding and remote sites. The Lords report called for a full inquiry into this endemic issue, noting how underfunding hampers police and agency coordination. Thames Valley Police deferred to the Environment Agency, underscoring fragmented responsibility.

Local voices amplify the urgency. Angler Billy Burnell, who fishes the Cherwell regularly, described the site as “horrific” and warned of an “environmental disaster waiting to happen.” Charity chief Laura Reineke demanded immediate action to prevent toxic run-off poisoning the Thames catchment, which supplies water to millions downstream.

Historical data reveals persistence. Fly-tipping incidents surged 20% year-on-year in England by 2024, per government figures, despite repeated policy pledges. Enforcement actions recovered just £2.5 million in fines last year against billions in economic damage from cleanup and pollution.

Systemic Burden on Rivers

The Cherwell, a Thames tributary, carries direct risks. Heat maps show the waste heating up, raising fire hazards on a floodplain prone to floods. Pollutants could leach into the river system within weeks, contaminating Oxford’s water supply and wildlife habitats.

This incident mirrors national patterns. Similar dumps have appeared in rural Lancashire and urban Essex this year, often near waterways. Councils nationwide report cleanup costs averaging £1 million per major site, straining budgets already cut by 40% since 2010.

Governments across parties have underinvested in waste infrastructure. Labour’s current administration inherited issues from Conservative predecessors, but both eras saw regulatory budgets slashed. The result: criminals exploit weak borders between legal and illegal disposal, with no overarching strategy to deter them.

Accountability dissolves in bureaucracy. No single body owns the response; agencies point to limited funds, ministers to legacies, and councils to national gaps. Perpetrators face fines averaging £400 per incident—peanuts against profits from evading landfill taxes, which hit £100 per tonne.

Broader economic toll mounts. Illegal dumping costs the UK £1 billion annually in remediation, per a 2023 National Audit Office estimate. This diverts funds from essential services, hitting rural economies hardest where tourism and fishing suffer from visible blight.

Local residents bear the fallout. Property values near Kidlington could drop 10-15% from pollution fears, based on similar cases in Kent. Anglers and farmers lose livelihoods as fish stocks decline and soil contaminates.

The pattern exposes institutional inertia. Functional governance would deploy rapid-response teams funded by targeted levies on waste producers, as in Germany’s model where recycling rates exceed 60%. Instead, UK systems reward delay, allowing crime to flourish unchecked.

Fly-tipping’s unchecked spread signals deeper environmental neglect in a nation once pioneering conservation. Institutions prioritize rhetoric over resources, leaving rivers poisoned and communities burdened. This grotesque heap beside the Cherwell embodies Britain’s slide: criminal opportunism fills voids carved by decades of underfunding and evasion.

Commentary based on Kidlington fly-tipping: Criminals dump mountain of waste in field at BBC News.