Nineteen Convictions, One Indefinite Stay

An Egyptian offender evades deportation via ECHR protections tied to familial extremism

A repeat criminal secures UK residency despite multiple offenses, as courts prioritize human rights over public safety. This ruling highlights persistent failures in deportation enforcement across political regimes.

A 24-year-old Egyptian man, who arrived in the UK in 2016, has secured the right to remain despite accumulating 19 criminal convictions, including robbery and assault on an emergency worker. Courts invoked the European Convention on Human Rights to block his deportation, citing risks tied to his father’s alleged Muslim Brotherhood affiliations. This outcome exposes a stark disconnect: immigration policy promises swift removal of foreign offenders, yet legal safeguards repeatedly override enforcement.

The man’s offenses span eight years, from possessing offensive weapons to burglary and drug crimes. He served prison time for one assault but faced no expulsion. Anonymity shields him, justified by mental health concerns, while his victims receive no such protection in public records.

Article 3 of the ECHR, prohibiting torture or inhuman treatment, underpinned the ruling alongside Article 8 on private and family life. Judges determined deportation to Egypt would endanger him due to familial extremist ties. This interpretation aligns with precedents where perceived risks in origin countries halt removals, even for repeat offenders.

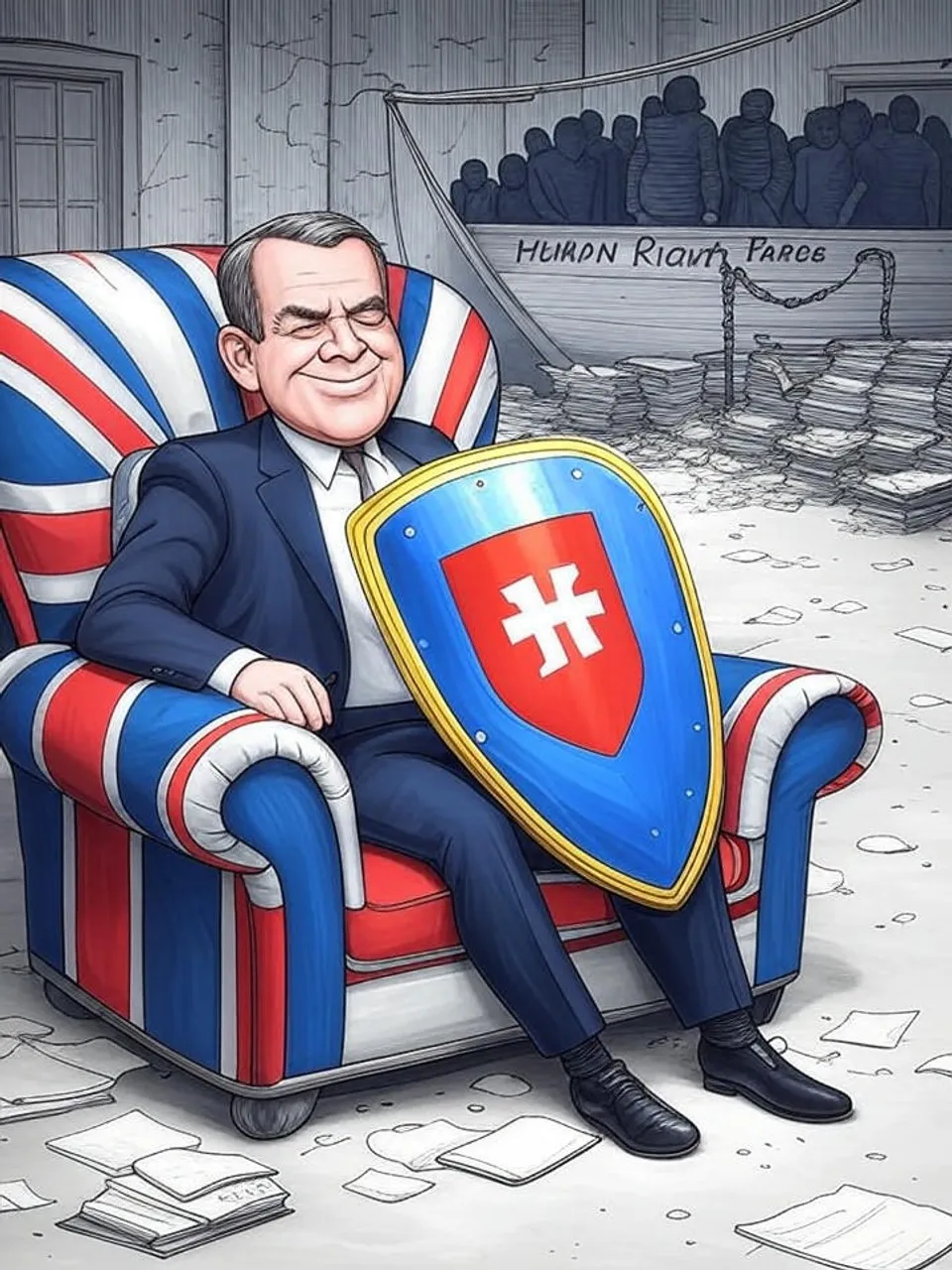

Conservative leaders now pledge ECHR exit, a policy formalized at their recent conference after a review by Lord Wolfson highlighted constraints on border control. Reform UK echoes this, demanding immediate withdrawal. Yet Labour’s Keir Starmer, who once authored guidance on leveraging the convention, maintains commitment, illustrating partisan divides that stall reform.

Deportation data reveals the scale: in 2023, only 3,926 foreign national offenders left the UK, per Home Office figures, against over 10,000 in custody. Backlogs in asylum and removal processes exceed 100,000 cases, with ECHR challenges succeeding in roughly 40% of appeals. This inefficiency persists across governments, from Blair’s 1997 expansions of human rights law to successive Tory delays on withdrawal.

Public safety bears the cost. The man’s crimes targeted UK residents, from robberies to assaults, yet policy frames him as the vulnerable party. Victims’ rights erode as courts prioritize international obligations, a reversal from pre-2000 eras when deportations proceeded without such hurdles.

Institutional inertia compounds the issue. The UK ratified the ECHR in 1951, incorporating it via the 1998 Human Rights Act under Labour. Tories promised repeal in 2010 but delivered partial tweaks; Labour’s 2024 manifesto vows retention. No administration has dismantled the framework, allowing cases like this to recur.

Economic strain follows: housing and support for retained offenders add to the £4.7 billion asylum budget shortfall reported last year. Taxpayers fund indefinite stays for those who offend, diverting resources from domestic priorities like policing. This misallocation reflects broader fiscal dysfunction, where migration controls fail to deliver promised savings.

Sovereignty claims falter under scrutiny. Eurosceptics decry ECHR as a Brussels imposition, yet the council operates from Strasbourg, and the UK helped draft it post-World War II. Withdrawal talks ignore Strasbourg’s oversight role, but even advocates admit alternatives like a British Bill of Rights remain unlegislated after years of consultation.

Judicial independence shields these rulings, but political accountability lags. Home Secretaries from both parties issue removal targets—10,000 annually under Sunak—yet miss them consistently. Officials rotate without consequence, perpetuating a system where enforcement yields to appeals.

This case underscores migration policy’s core pathology: stated goals of control clash with embedded legal barriers. Ordinary citizens face heightened risks from unremoved criminals, while governments trade barbs over the ECHR without action. Britain’s border integrity frays not from external forces alone, but from internal commitments that privilege abstract rights over tangible security, a decline etched in every unheeded conviction.

Commentary based on Asylum farce as man wins court fight to stay in Britain on human rights grounds despite committing 19 crimes since arriving at GB News.