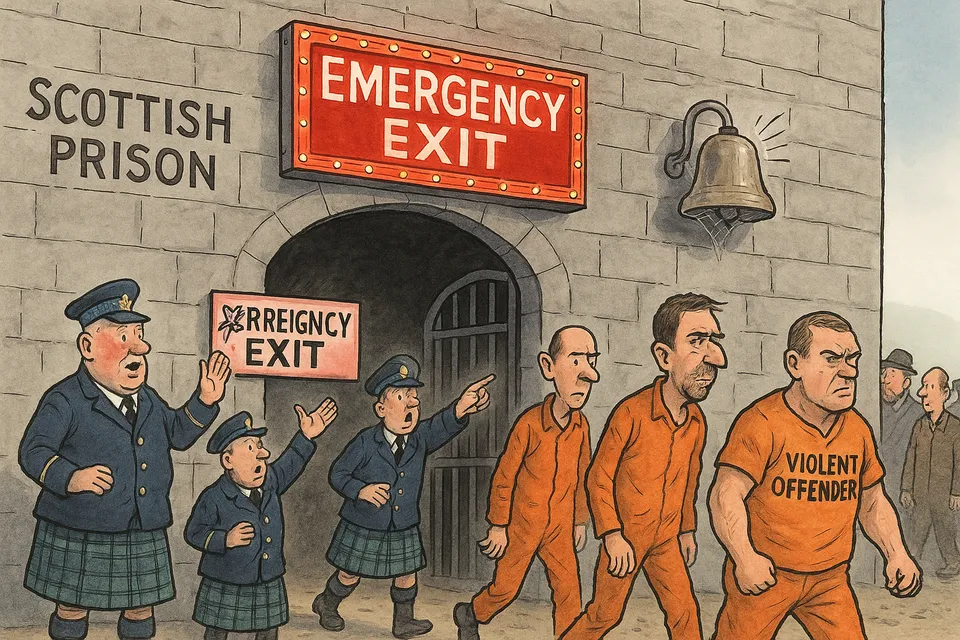

Scotland's Prison Crisis: Violent Criminals Released Early as System Collapses

How Emergency Measures Become Institutional Normalization

Scotland has just admitted it can no longer perform one of the state's most basic functions: keeping violent criminals in prison for their court-ordered sentences. In February and March 2025, authorities released 312 inmates—including 152 violent offenders—after serving just 40% of their terms, down from an already inadequate 50% threshold established months earlier.

Officials presented this mass early release as an “emergency measure,” the same emergency that required identical measures last summer, and the same emergency that will require them again within months. When emergencies become routine, they cease to be emergencies and become admissions of systematic failure—the normalization of institutional collapse disguised as responsible crisis management.

What they claim: Scottish authorities describe early prisoner releases as “proportionate emergency measures” providing temporary “respite” from acute pressure, with most inmates released just months ahead of their scheduled dates.

What is happening: Scotland has abandoned the basic state function of enforcing court-ordered sentences, releasing violent criminals after serving 40% of their terms because the system cannot cope with its fundamental responsibilities.

A System Eating Itself

The numbers reveal an institution trapped in a cycle of managed decline. Scotland operates 17 prisons with a combined design capacity of 7,805 inmates. Current population: 8,136. Eight facilities now operate at “red risk status”—a bureaucratic euphemism meaning they’re struggling to cope with basic operational demands.

But the crisis extends beyond mere overcrowding. The Scottish Prison Service’s own data exposes the futility of their approach. In summer 2024, they released 477 prisoners early. Within two months, the prison population had climbed back above the level that triggered the releases in the first place. Of those 477 early releases, 61 reoffended and returned to custody before their original release dates would have expired.

The February-March 2025 releases followed an identical pattern: declare emergency, release prisoners, watch population climb again, declare emergency, repeat. This isn’t crisis management—it’s institutional surrender disguised as policy.

Numbers Don’t Lie

The breakdown of early releases reveals the scale of compromise required to keep the system functioning:

Criminal Categories Released Early:

- 152 violent offenders (non-sexual crimes of violence)

- 69 convicted of “crimes against society”

- 52 serving sentences for dishonesty offences

- Remainder: various other categories

Release Demographics:

- 92% male

- Majority serving 1-2 year sentences

- Average early release: less than 3 months ahead of schedule

- Excluded categories: domestic abuse and sexual offences

HMP Barlinnie, Scotland’s largest prison, released the highest number (65) under this scheme. Barlinnie has become synonymous with overcrowding and operational dysfunction—a facility designed for rehabilitation that now functions as a pressure valve for systemic failure.

The Scottish government’s response reveals the depth of institutional dysfunction. Rather than addressing root causes, they’ve normalized crisis management. The SPS budget increased 10% to £481.5 million in 2025-26—not for expansion or improvement, but simply to manage decline. Early release thresholds dropped from 50% to 40% of sentences, a 20% reduction in actual time served.

UK-Wide Institutional Decay

Scotland’s prison crisis mirrors broader patterns of institutional failure across the UK. England and Wales released over 1,700 prisoners early in autumn 2024 using identical emergency provisions. The same causes produce the same failures: underfunding, poor planning, political short-termism, and bureaucratic inertia.

This represents a fundamental shift in how British institutions operate. Previous generations built systems designed to fulfill their stated purposes. Current institutions exist primarily to manage their own dysfunction while maintaining the appearance of functionality.

The Recurring Cycle:

- Institution reaches crisis point due to chronic underfunding/mismanagement

- Declare emergency and implement temporary measures

- Crisis temporarily abates

- No structural changes implemented

- Crisis returns, often worse than before

- Repeat with increasingly desperate measures

This pattern repeats across health services, education, transport, and housing. The prison system isn’t unique—it’s simply more visible because failure has immediate public safety implications.

Beyond Political Spin

Both Scottish and UK governments present early releases as “proportionate responses” to temporary pressures. This language obscures the fundamental question: how did a basic state function—keeping convicted criminals in prison for their full sentences—become impossible to maintain?

The Real Questions:

- Why do facilities built for 7,805 inmates suddenly require housing for 8,136+?

- How did prison population forecasting become so inadequate that “emergencies” occur every few months?

- What deterrent effect remains when violent offenders serve 40% of already-reduced sentences?

- Why do the same problems persist regardless of which party holds power?

The answers reveal systemic breakdown that transcends normal political categories. This isn’t about tough-on-crime versus rehabilitation philosophy. It’s about institutional competence—the basic ability to plan, build, and operate essential services.

What Decline Looks Like

The Scottish Prison Service spokesperson’s statement inadvertently captured the essence of institutional decline: “staff unable to do the critical work of building relationships and supporting rehabilitation, and prisoners frustrated by the impact on their daily lives and the opportunities available to them.”

This describes an institution that has abandoned its core mission. Prisons exist to protect public safety and, where possible, rehabilitate offenders. When overcrowding prevents both functions, the institution becomes merely a temporary holding facility—expensive, ineffective, and counterproductive.

Systemic Indicators of Decline:

- Normalized Crisis Management: Emergency measures become routine policy

- Function Abandonment: Institutions stop attempting their stated purposes

- Managed Decline: Resources focus on containing dysfunction rather than solving problems

- Accountability Void: No individuals face consequences for systemic failure

- Public Acceptance: Citizens adapt expectations downward to match degraded reality

Strip away the bureaucratic language and political spin, and the facts are stark: Scotland can no longer keep violent criminals in prison for their full sentences. This isn’t a temporary setback or resource allocation dispute—it’s fundamental state failure at one of government’s most basic responsibilities.

For Citizens, This Means:

- Violent offenders serve 60% less time than their sentences specified

- Repeat offenders return to communities months ahead of schedule

- Prison sentences become essentially meaningless as deterrents

- Public safety is subordinated to administrative convenience

- The justice system promises protection it cannot deliver

For Institutions, This Reveals:

- Planning failures spanning multiple government cycles

- Inability to forecast basic operational requirements

- Preference for crisis management over structural solutions

- Bureaucratic self-preservation prioritized over public service

- Democratic accountability mechanisms functioning poorly or not at all

How We Got Here

The current crisis didn’t emerge overnight. Scotland’s prison population has grown steadily while capacity remained static. Sentencing policies increased average sentence lengths while successive governments delayed necessary capacity expansion. The result was entirely predictable—and entirely predicted.

Previous generations of officials would have viewed early release of violent offenders as professional and political suicide. Current officials present it as responsible crisis management. This shift in acceptable failure represents a broader cultural change within British institutions—from competence as expectation to dysfunction as norm.

The Uncomfortable Truth

The most damaging aspect of Scotland’s prison crisis isn’t the early releases themselves—it’s the institutional acceptance that this represents normal operation. When emergency measures become routine policy, when basic state functions become impossible to maintain, when failure is rebranded as responsible management, the institution has ceased to function as intended.

Scotland’s prisons now operate as pressure valves for political failure rather than instruments of justice. They release prisoners not when rehabilitation is complete or sentences are served, but when operational pressures become unbearable. This represents the subordination of justice to bureaucratic convenience—a fundamental reversal of institutional purpose.

Institutional Collapse as Policy

The Scottish prison crisis exemplifies a broader pattern across UK institutions: the normalization of failure and the abandonment of core functions. Whether it’s NHS waiting lists, education standards, transport reliability, or housing provision, British institutions increasingly exist to manage their own dysfunction rather than serve their stated purposes.

This isn’t about political ideology or spending levels—though both matter. It’s about institutional culture that has adapted to accept failure as inevitable and crisis management as leadership. When institutions stop attempting their core functions and focus instead on managing expectations downward, they become obstacles to rather than instruments of public welfare.

Documenting Descent

Scotland’s prison crisis offers a clear view of how institutional decline operates in practice. Emergency powers normalize. Standards erode gradually then suddenly. Core functions become optional. Crisis management replaces strategic thinking. Public safety becomes subordinate to administrative convenience.

The Scottish Prison Service will continue releasing inmates early because the alternative—actually solving the capacity crisis—requires the kind of long-term planning and resource commitment that British institutions have proven incapable of delivering. The cycle will repeat because the system now depends on crisis management to function at all.

This isn’t just about prisons or Scotland. It’s about what happens when institutions abandon their core purposes and adapt instead to manage their own decline. The early release of violent offenders becomes routine. The emergency becomes permanent. The exception becomes the rule.

That’s what decline looks like in practice: not dramatic collapse, but gradual abandonment of basic functions until failure becomes policy and crisis becomes routine. Scotland’s prisons aren’t broken—they’re working exactly as British institutions now work, which is to say, badly and getting worse.

Commentary based on More than 150 violent offenders released early in Scotland at BBC News.