The Anatomy of Extraction: How Thames Water Turned Emergency Aid Into Executive Enrichment

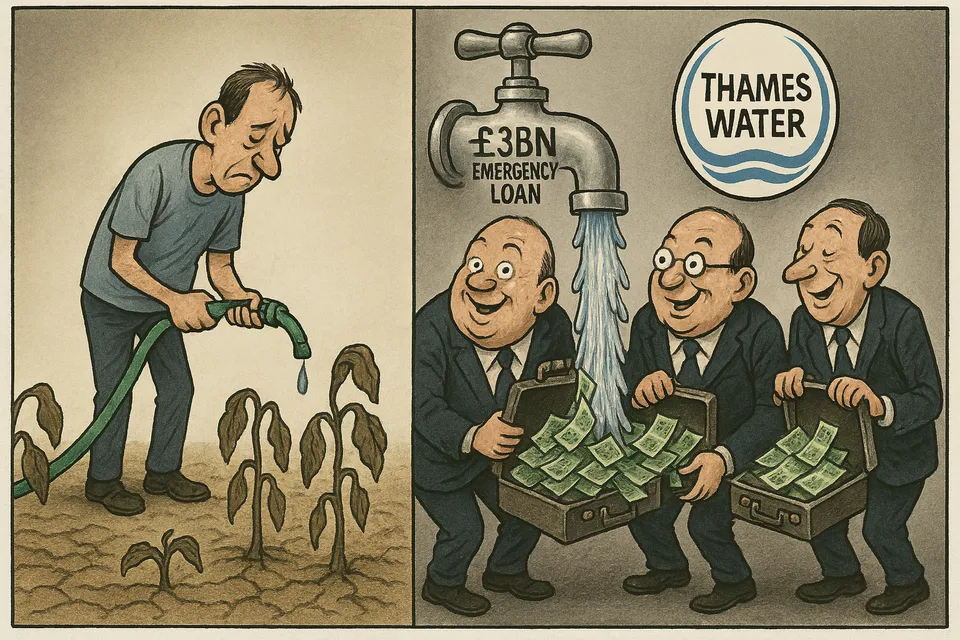

Thames Water's executives pocketed £15.7m in bonuses while 16 million customers face hosepipe bans.

While 16 million customers face hosepipe bans this summer, Thames Water's executives have successfully converted a £3bn emergency lifeline into personal windfalls totaling £15.7m. The company that can't maintain water supplies during a shortage somehow found £2.46m to pay 21 managers in April—from funds meant to prevent corporate collapse.

Commentary Based On

The Guardian

Thames Water refuses to claw back bonuses paid using £3bn emergency loan

Thames Water paid retention bonuses averaging £117,000 per manager from an emergency loan carrying a 9.75% interest rate. The same managers will receive identical payments in December, then share £10.8m next June—assuming the company survives that long.

Four executives earning up to £400,000 annually stand to collect £1.13m each—nearly three years’ salary—for simply remaining at their posts during the company’s death spiral.

The water regulator, Ofwat, learned about these payments after they were distributed. The environment secretary requested clawbacks. The company’s board refused. Parliament expressed outrage. Nothing changed.

Meanwhile, Thames warned households to prepare for water restrictions because infrastructure investment has been systematically neglected while debt ballooned to £15bn under private ownership.

How Failure Gets Rewarded

The mechanics of this scheme reveal how UK institutions have been reprogrammed to serve extraction rather than service delivery. When Parliament passed legislation banning performance bonuses for water executives, Thames simply relabeled them “retention payments” with “no performance-related element.”

Board minutes explicitly confirm this maneuver was designed to circumvent the Water (Special Measures) Act. The same document describes these managers as Thames’s “most precious resource”—more precious, apparently, than maintaining water supplies or preventing sewage discharges.

Sir Adrian Montague, Thames’s chair, initially told MPs that creditors “insisted” on these payments. When challenged, he admitted this was false. No consequences followed. The payments continue.

The Pattern of Plunder

Thames Water exemplifies how essential infrastructure has been transformed into vehicles for financial engineering. Since privatization in 1989:

- Debt increased from zero to £15bn

- Dividends of £7.2bn were extracted

- Infrastructure deteriorated to crisis levels

- Regulatory fines became a cost of doing business

- Executive compensation soared while service quality plummeted

The current “rescue” follows the same template. Hedge funds and investment firms—including Aberdeen, M&G, and Elliott Management—provided the £3bn loan at punitive rates. These same creditors now position themselves to take ownership, having already extracted billions through previous debt arrangements.

The privatization promise was efficiency through competition. The reality: monopoly utilities converted into debt-extraction machines, with captive customers funding both operational failures and executive enrichment.

Regulatory Theater

Ofwat’s response encapsulates UK regulatory decay. Chief executive David Black expressed “disappointment at the lack of transparency”—as if transparency were the issue when executives raid emergency funds while infrastructure crumbles.

The regulator suggests broadening bonus restrictions by 2027, conveniently after current executives have collected their windfalls. No enforcement action. No financial penalties. No executive accountability. Just expressions of disappointment and promises of future rule changes that will inevitably be gamed.

This isn’t regulation—it’s choreographed ineffectiveness. Ofwat has the power to block these payments but chooses procedural hand-wringing instead. The Department for Environment continues to “expect” Ofwat to act, creating circular buck-passing while millions flow to executives.

Political Paralysis

Steve Reed, the Environment Secretary, exemplifies political capture. Despite public outrage and parliamentary pressure, his response amounts to writing letters “expecting” action from a regulator that has already demonstrated its unwillingness to act.

The government could impose immediate restrictions, mandate clawbacks, or simply renationalize Thames Water tomorrow. Instead, ministers hide behind the fiction of regulatory independence while executives convert public necessity into private wealth.

This paralysis isn’t accidental. It’s the predictable result of a system where political careers depend on not disturbing corporate interests, where regulatory positions are stepping stones to industry roles, where the consequences of confrontation exceed the costs of acquiescence.

The Extraction Equation

The numbers tell the story:

- Emergency loan: £3bn at 9.75% interest

- Executive bonuses: £15.7m over 14 months

- Average bonus per manager: £748,000

- Customers facing restrictions: 16 million

- Accountability delivered: Zero

Each manager will receive more in “retention” payments than most UK households earn in two decades. They’re being paid premium rates to oversee failure—retained not despite the crisis but because of it. Crisis creates opportunity for those positioned to exploit it.

What This Really Means

Thames Water isn’t failing—it’s succeeding at its actual purpose: transferring wealth from captive customers to financial operators. The infrastructure decay, service failures, and environmental damage aren’t bugs in the system. They’re features.

When essential services can be financialized, when regulators won’t regulate, when politicians won’t act, when media treats each scandal as isolated rather than systemic—this is the inevitable result. Not corruption in the traditional sense, but something worse: a system operating exactly as redesigned.

The UK’s water infrastructure joins energy, rail, healthcare, and housing in the same extractive spiral. Public goods reconstituted as private assets. Citizens reduced to revenue streams. Decline repackaged as shareholder value.

Thames Water’s executives aren’t uniquely greedy. They’re rational actors in a system that rewards extraction over service, financial engineering over actual engineering, managed decline over genuine improvement. They’re simply following the incentives we’ve allowed to be constructed.

The surprise isn’t that they’re taking the money. The surprise would be if they didn’t. In broken Britain, failure has never been more profitable.

Commentary based on Thames Water refuses to claw back bonuses paid using £3bn emergency loan by Helena Horton and Jasper Jolly on The Guardian.