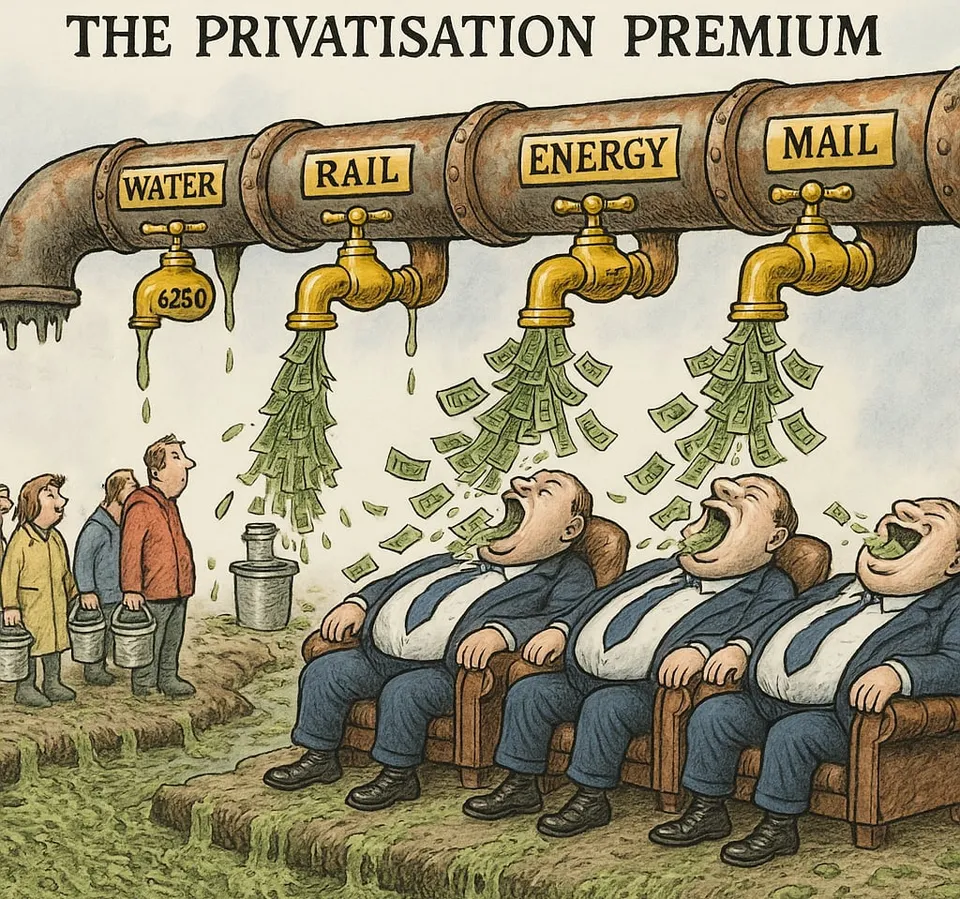

The £200 Billion Extraction: How Privatisation Became Britain's Longest-Running Wealth Transfer

Four decades of privatisation have funneled £193bn from UK households to shareholders, while infrastructure decays and bills soar.

Since 1991, £193 billion has been extracted from British households and transferred to shareholders of privatised utilities, while promised competition and efficiency delivered polluted rivers, unreliable trains, and soaring bills. This isn't a policy debate anymore. It's a measurable wealth transfer operating at industrial scale.

Commentary Based On

The Guardian

UK public has paid £200bn to shareholders of key industries since privatisation

Margaret Thatcher sold privatisation as creating a “shareholder democracy” where ordinary Britons would own stakes in their essential services. Four decades later, the actual outcome is documented: £193 billion extracted from British households and transferred to shareholders since 1991, while the promised competition and efficiency delivered polluted rivers, unreliable trains, and soaring bills.

This isn’t a policy debate anymore. It’s a measurable wealth transfer operating at industrial scale.

The Numbers That Matter

Common Wealth’s analysis reveals the mechanics of extraction with clinical precision. Since privatisation began, shareholders have taken £88.4 billion from water companies that simultaneously ran up £73 billion in debt and presided over record sewage spills. Energy network companies operated with 55% profit margins between 2020-24, compared to the FTSE 100 average of 15%. Rolling stock companies paid dividends equivalent to 102% of their post-tax profits over eight years.

The extraction accelerates rather than moderates. In the past decade alone, £114.6 billion flowed from customer bills to shareholders. That’s £250 per household per year since 2010 - what researchers call the “privatisation premium.” This premium buys nothing except shareholder returns.

Consider the velocity of Britain’s privatisation compared to other nations. Between 1981 and 1996, the UK shed public wealth at 7.4% of national income annually for fifteen years. Only Russia, Hungary and the Czech Republic during their post-communist “shock therapy” privatised faster. Britain chose to dismantle its public infrastructure at a pace matched only by collapsing communist states.

The Infrastructure Reality

The promise was that private ownership would deliver investment and efficiency. The data shows the opposite. Energy investment as a share of GDP was 1.15% under public ownership from 1950-79. Under privatisation from 1991-2024, it collapsed to 0.48%. Investment halved while bills soared.

Water companies exemplify this pattern. They’ve accumulated £73 billion in debt not through infrastructure investment but through financial engineering designed to maximise shareholder returns while loading companies with borrowing. Thames Water stands on the brink of collapse, its infrastructure crumbling while its owners extracted billions.

Rail tells the same story. Half the industry’s income in 2023-24 came from taxpayers through subsidies, yet profits flow to private shareholders. The public pays twice - once through taxes, again through fares - while service deteriorates. One in five commercial bus services disappeared since 2019 alone.

The Extraction Architecture

What Common Wealth documents isn’t market failure. It’s market success - for shareholders. The privatised utilities operate as extraction machines, converting essential service monopolies into wealth transfer mechanisms. Energy network companies don’t compete; they operate regional monopolies with guaranteed returns. Water companies can’t lose customers; they extract maximum value while infrastructure decays.

Directors across these privatised sectors awarded themselves £662.8 million in pay packages from 2020-24. Meanwhile, families face choosing between heating and eating while sewage flows into rivers and trains don’t run.

The comparison with other wealthy nations exposes Britain’s outlier status. Most advanced democracies maintain public ownership of essential services. They recognise what Britain’s political class refuses to acknowledge: some services are too essential for profit extraction.

The Political Abdication

Keir Starmer campaigned for Labour leadership promising “common ownership of rail, mail, energy and water.” Once in power, he abandoned these commitments, ruling out nationalisation despite YouGov polling showing majority public support for returning utilities to public ownership. The political class, regardless of party, protects the extraction system.

Labour’s minimal moves - bringing some train operators into public ownership, creating GB Energy - represent token gestures against a £7.2 billion annual wealth transfer. They’re applying plasters to a haemorrhage.

The successful counter-examples make the failure starker. Nottingham’s publicly-owned bus company delivers reliable service. Greater Manchester’s public transport integration under Andy Burnham shows what’s possible. These aren’t radical experiments; they’re normal governance in most developed nations.

The Decline Pattern

This isn’t simply about utility bills or service quality. It’s about how Britain systematically transfers wealth from citizens to shareholders through essential service monopolies. The privatisation of natural monopolies created permanent extraction mechanisms that function regardless of service quality, investment levels, or public need.

Professor Ewan McGaughey states the choice plainly: “We can keep paying billions to foreign banks and shareholders that control our privatised services, or we can have faster mail and transport, clean energy and water, for lower cost. But we cannot do both.”

Britain chose the first option and continues choosing it daily. Every water bill funds dividends while sewage pollutes beaches. Every energy payment enriches shareholders while investment stagnates. Every rail fare subsidises private profit while services deteriorate.

The Bigger Picture

The £193 billion extraction since 1991 represents more than a policy failure. It exemplifies how Britain’s governing institutions facilitate wealth transfer from citizens to capital owners through essential services. The promise of market efficiency delivered neither markets nor efficiency - just extraction.

When energy network companies maintain 55% profit margins on essential infrastructure, when water companies pay £88 billion in dividends while accumulating £73 billion in debt, when half of rail income comes from taxpayers while profits flow to shareholders, we’re not observing market economics. We’re documenting systematic rent extraction from captive populations.

The privatisation premium isn’t a bug in the system. It’s the system working as designed - transferring wealth upward through essential service monopolies while infrastructure decays and services deteriorate. Every political leader since Thatcher has maintained this architecture. Every promise of reform evaporates once in office.

Britain didn’t just sell its public assets. It created permanent extraction mechanisms that turn essential services into wealth pumps, moving money from households to shareholders regardless of performance, investment, or public benefit. The £200 billion already extracted is just the beginning. The meters keep running, the bills keep rising, and the transfer continues.

This is what decline looks like: not dramatic collapse but systematic extraction, maintained by political consensus, operating through essential service monopolies, transferring wealth from citizens to shareholders while infrastructure crumbles and services fail. The numbers are documented. The pattern is clear. The extraction continues.

Commentary based on UK public has paid £200bn to shareholders of key industries since privatisation by Matthew Taylor, Sandra Laville on The Guardian.