The Casey Report: When Institutions Prefer Ignorance to Accountability

How Grooming Gangs Expose Britain's Institutional Decay

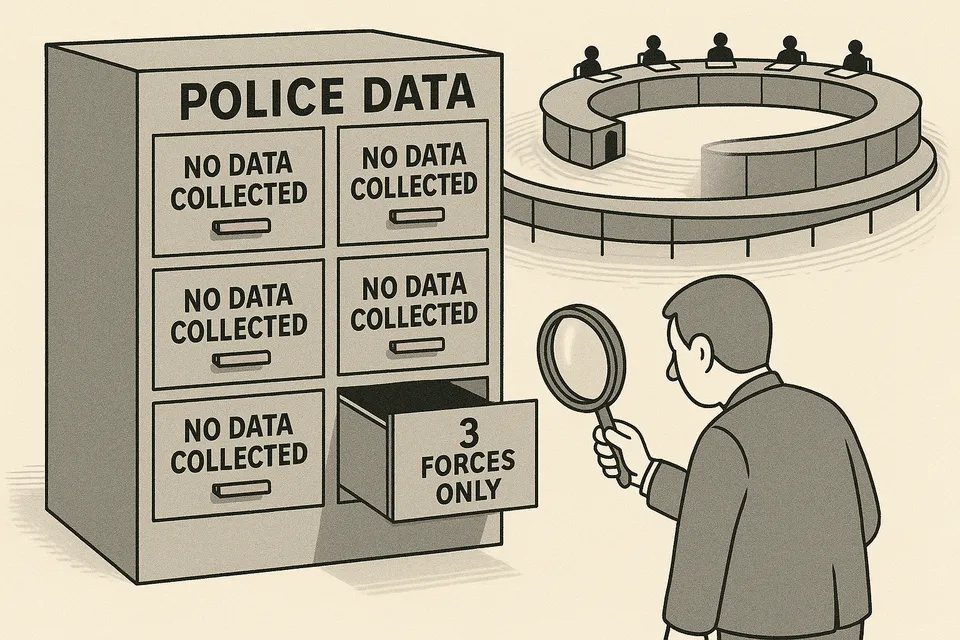

Louise Casey's grooming gangs report has revealed a truth more damaging than the crimes it investigates: Britain's institutions have systematically avoided collecting the data necessary to understand and address widespread child sexual exploitation. Two-thirds of police forces have failed to record the ethnicity of perpetrators, creating what Casey diplomatically terms a "culture of ignorance."

What they claim: British institutions have been diligently investigating grooming gangs and collecting data to protect vulnerable children from systematic abuse.

What actually happened: Two-thirds of police forces have failed to record basic ethnicity data about perpetrators, creating what Casey calls a “culture of ignorance,” while launching another expensive multi-year inquiry instead of the criminal investigations that could deliver actual accountability.

Casey could only extract usable data from three police forces. Three. In a country where grooming gang scandals have dominated headlines for over a decade, the vast majority of forces have somehow failed to record basic information about perpetrators.

This represents a fundamental operational failure. When institutions cannot or will not collect elementary data about serious crimes, they have abandoned their core function. The pattern suggests deliberate avoidance rather than administrative incompetence.

From the limited data available, Casey found suspects were “disproportionately likely to be Asian men.” Yet this conclusion required piecing together fragments from just three forces and publicly available court reports. The institutional preference for ignorance over evidence could hardly be clearer.

The Inquiry Industrial Complex

Britain now faces its latest expensive, multi-year investigation into grooming gangs. This follows a seven-year national statutory inquiry led by Professor Alexis Jay that involved over 7,000 victims and survivors and already examined institutional responses to child sexual exploitation.

Nazir Afzal, the prosecutor who secured convictions in the Rochdale case, captured the essential futility: “People want accountability. I’m not sure people’s expectations will be realised. Only criminal investigations can bring real accountability.”

The cycle is predictable: scandal emerges, inquiry launched, recommendations made, little changes, scandal re-emerges. Each inquiry serves as institutional theatre—demonstrating concern while avoiding the criminal investigations that might actually deliver consequences.

Political Calculation Over Evidence

Keir Starmer’s journey from refusing a national inquiry in January to accepting Casey’s recommendation reveals the primacy of political calculation over evidence-based governance. The Guardian notes Starmer was “caught on the hop” and forced into what appears to be a “damaging U-turn.”

The initial refusal wasn’t based on evidence or victim needs—it was because the demand came from Elon Musk, backed by Conservatives and Reform. The subsequent acceptance followed Casey’s report, providing political cover for the same action.

This pattern—reactive governance driven by political positioning rather than proactive evidence-gathering—exemplifies institutional decay. Competent governance would have launched proper investigations immediately upon taking office, using the opportunity to demonstrate serious intent on a long-neglected issue.

The Community Tensions Excuse

Throughout Casey’s findings runs a persistent concern about “community tensions” and potential “civil unrest.” The article notes risks of “smearing Asian and Pakistani males as potential paedophiles” and references last summer’s riots.

These are legitimate concerns. But they also reveal how institutional priorities work in practice: social cohesion trumps truth-seeking, community relations override victim protection, and fear of difficult conversations enables continued ignorance.

Casey herself recognised this dynamic: “If good people don’t grip difficult issues, in my experience bad people do.” Yet Britain’s institutions have spent decades demonstrating they prefer not to grip difficult issues at all.

The Accountability Vacuum

The most revealing aspect of this saga is what it exposes about institutional accountability. Decades of failures across police forces, social services, and local councils have produced extensive documentation but minimal consequences.

The forthcoming inquiry will examine “policies and decisions made by social workers and youth workers employed by predominantly Labour councils” and question “what local MPs – often Labour MPs – knew.” Yet past experience suggests these examinations will generate recommendations rather than prosecutions, reports rather than responsibility.

As Afzal noted, criminal investigations deliver accountability. Everything else is institutional displacement activity.

The Systemic Pattern

The grooming gangs scandal exemplifies a broader pattern of UK institutional dysfunction: the systematic avoidance of uncomfortable truths, the preference for process over outcomes, and the substitution of inquiries for accountability.

Whether examining the Post Office scandal, building safety failures, or financial services misconduct, the same pattern emerges. Institutions discover problems, commission investigations, produce reports, and implement procedures—while those responsible continue in post and victims remain without justice.

The Reality Check

Casey’s report documents not just the abuse of vulnerable children, but the institutional culture that enabled it to continue. The data vacuum wasn’t accidental—it was the predictable result of institutions prioritising their comfort over their duty.

Three years from now, when Casey’s recommended inquiry concludes, Britain will likely possess another substantial report documenting institutional failures. Whether it will possess institutional accountability remains, based on all available evidence, highly doubtful.

The true scandal isn’t just what happened to those children. It’s that Britain’s institutions have demonstrated they prefer not to know what happened, not to record what’s happening, and not to hold anyone accountable for either.

This is decline by design, not accident.

Commentary based on Motability won’t give up its lucrative business without a fight by Lana Hempsall on The Spectator.