The Well Has Run Dry: Victorian Engineers Built 11 Reservoirs. We Can't Build One

Britain Can't Even Build Reservoirs Anymore

Yorkshire Water manages 120 reservoirs, most built by Victorian city corporations or in the post-war reconstruction era. Thruscross was constructed in the 1960s. Grimwith was expanded in 1982. Then, shortly after water privatization in 1989, construction simply stopped.

The numbers tell a story of institutional paralysis. Yorkshire Water manages 120 reservoirs, most built by Victorian city corporations or in the post-war reconstruction era. Thruscross was constructed in the 1960s. Grimwith was expanded in 1982. Then, shortly after water privatization in 1989, construction simply stopped.

The government announced nine new reservoirs by 2050 last year. Not one will be operational for at least a decade. In the same timeframe that Victorian engineers built entire networks of reservoirs—flooding valleys, relocating villages, laying hundreds of miles of pipes—modern Britain cannot complete a single project.

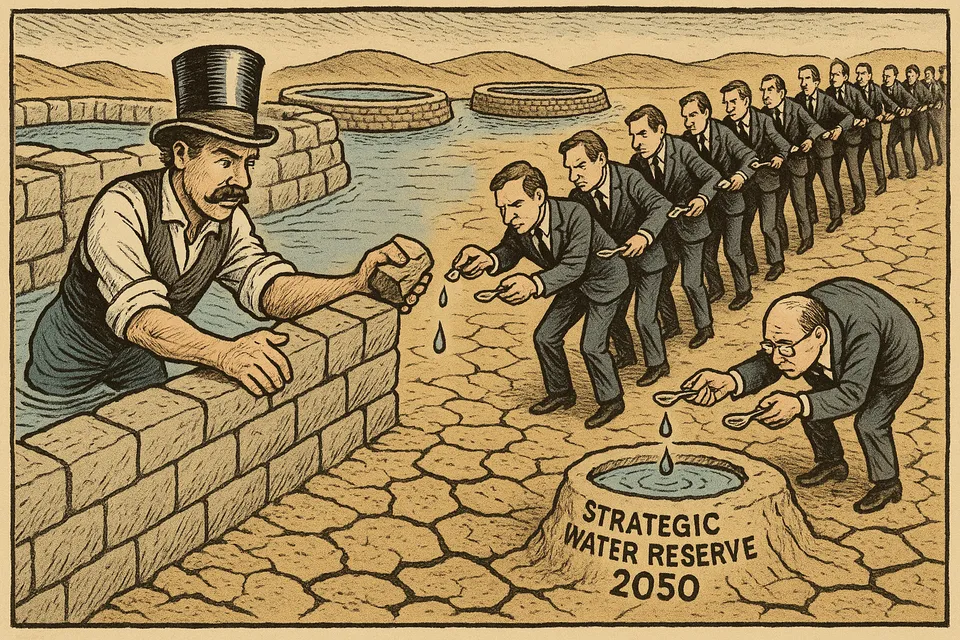

Consider what our ancestors achieved: Bradford Corporation built 11 reservoirs. Leeds Waterworks created multiple sites across the Washburn Valley in the 1870s. Sheffield constructed four reservoirs in Bradfield before 1900. They did this without environmental impact assessments, computer modeling, or modern construction equipment. They simply identified needs and built solutions.

The Excuses Reveal the Decline

Yorkshire Water’s spokesperson offered a revealing list of why building reservoirs is now “challenging”: cost, finding suitable sites, planning constraints, environmental impact, and community opposition. Every one of these obstacles existed for the Victorians. They built anyway.

Dr Kevin Grecksch of Oxford notes that “big environmental protest groups didn’t exist” in the 1950s. But neither did the machinery, technology, and accumulated engineering knowledge we possess today. The real difference isn’t capability—it’s institutional will and competence.

The planning system has become a mechanism for preventing construction rather than enabling it. Seven proposed reservoirs will be designated Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects, moving decisions above local authority level. Yet even this attempt to bypass local obstruction comes with warnings about “excluding the public” from Dr Grecksch. The system is paralyzed by its own processes.

The Pattern of Managed Decline

Water privatization in 1989 marks a precise turning point. The last major reservoir completion in 1992 represents the final echo of public sector planning. Since then, water companies have focused on financial engineering rather than actual engineering. Dividends flow more reliably than new infrastructure.

Yorkshire Water did manage to build a ring main pipe system in the mid-1990s to move water from east to west. They can build two new boreholes. They can construct “new water treatment works.” What they cannot do is what Victorian city corporations did routinely: identify a valley, acquire the land, build a dam, and create new water storage capacity.

The government’s solution perfectly captures modern British governance: announce a target (nine reservoirs by 2050), create a new bureaucratic designation (NSIP), and defer actual construction beyond any reasonable accountability timeframe. By 2050, the politicians making these promises will be long retired, the civil servants pensioned off, and the water company executives moved on to other directorships.

What This Really Means

When a nation cannot build basic infrastructure that its great-great-grandparents constructed routinely, it reveals fundamental institutional decay. The skills exist. The technology is superior. The need is obvious. The money, we’re told, is available. Yet nothing happens.

Instead, we get Dr Klaar suggesting “water reuse schemes” and “thinking about reusing water much more smartly.” Dr Grecksch advocates for “measures to simply save a little bit of water.” These are the solutions of a society that has given up on actually building things. The Victorians didn’t tell Manchester to reuse its water more smartly—they built Thirlmere Reservoir and a 96-mile aqueduct.

The Yorkshire Water spokesperson’s language is particularly revealing: they’re “reflecting on the rapid effects of climate change” and “thinking and planning for how we can meet future needs.” Reflecting. Thinking. Planning. These are the activities of institutions that have forgotten how to act.

The Bigger Picture

Britain’s inability to build reservoirs isn’t unique—it’s symptomatic. We can’t build nuclear power stations (Hinkley Point C is now seven years late). We can’t build railways (HS2’s northern leg was cancelled). We can’t build roads, airports, or houses in the quantities needed. The country that pioneered the Industrial Revolution now pioneersprocess and paralysis.

Climate change isn’t a surprise. Population growth isn’t unexpected. The need for water infrastructure has been obvious for decades. Yet Britain responds to predictable challenges with “reflection” and “consideration” while Yorkshire’s reservoirs sit half empty and the government promises solutions that won’t arrive until 2050—if ever.

The Victorians built infrastructure for cities they were creating and populations they were anticipating. They embedded such surplus capacity that their reservoirs still supply much of Britain’s water 150 years later. We can’t even maintain what they built, let alone match their ambition. That’s not progress. That’s decline, documented in every missing reservoir, every postponed project, every promise deferred to a conveniently distant future.

The next time politicians speak of Britain as a global leader in climate adaptation or infrastructure, remember this: we literally cannot build the basic water storage that every previous generation of Britons managed without difficulty. The rhetoric of national greatness masks an reality of institutional incapacity. The reservoirs aren’t being built because modern Britain has forgotten how to build.

Commentary based on Why is it so difficult to build new reservoirs? by Jessica Bradley on BBC News.