The Two-Hour Window: How British Transport Police Decriminalised Bike Theft

How a Policy Change Reveals Deeper Institutional Failures in UK Policing

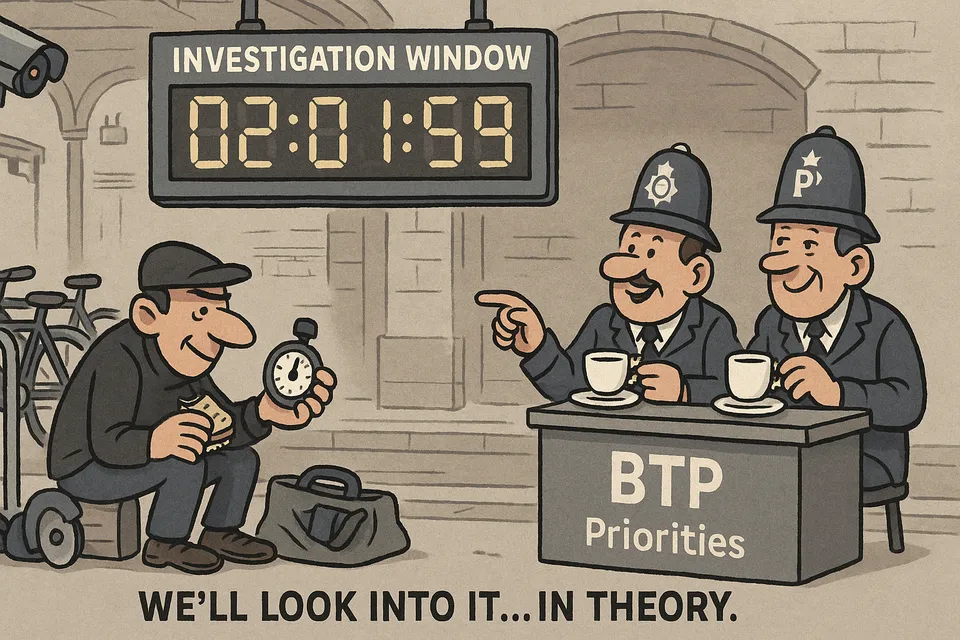

British Transport Police have effectively legalised bicycle theft at railway stations by refusing to investigate thefts of bikes left for more than two hours. This policy, which applies even to bikes stolen from secure parking facilities with CCTV coverage, reveals a deeper institutional failure. By prioritising "crimes which cause the most harm," BTP has created an environment where bike theft is rampant and commuters are left unprotected. This analysis explores how this policy reflects broader issues in UK governance and public service delivery.

British Transport Police have introduced a policy that effectively legalises bicycle theft at railway stations. If your bike has been parked for more than two hours, the theft will not be investigated. CCTV footage will not be reviewed. Officers will not be assigned. The crime simply won’t be examined.

This applies even when bikes are stolen from supposedly secure parking facilities with dedicated CCTV coverage that commuters pay to use. The policy also extends to car thefts and train thefts, with similarly arbitrary restrictions.

The rationale provided: officers need their time for “crimes which cause the most harm.”

The Numbers That Matter

Consider what this policy actually covers. Commuters routinely leave bicycles at stations for 8-10 hours during a working day. The British Transport Police have created a two-hour threshold that captures almost none of actual commuting patterns.

Thousands of bicycles are stolen from stations annually. Under this policy, the vast majority now fall outside investigation parameters. Any bike worth under £200 is automatically excluded, regardless of circumstances.

The result is measurable. Simon Feldman, a commuter at Watford Junction, had his bicycle stolen while working a 10-hour shift in London. The theft occurred directly under CCTV cameras. British Transport Police informed him they would not investigate because he had left the bike for more than two hours.

What The Policy Reveals

This is not a resource allocation decision. This is institutional failure dressed as prioritisation.

First, examine the infrastructure investment. Public money has been spent building secure bike parking facilities at stations, complete with CCTV systems. These facilities are now functionally worthless. The cameras record crimes that will never be investigated. The security is theater, not protection.

Second, consider the incentive structure created. Thieves can operate with near-total impunity. As Feldman notes, criminals now take bikes in broad daylight because they understand the enforcement vacuum. The policy doesn’t just fail to deter crime, it actively encourages it by signalling zero consequences.

Third, observe the arbitrary nature of the threshold. Why two hours? The decision bears no relationship to how citizens actually use railway infrastructure. It appears designed primarily to minimise BTP workload rather than address the actual problem.

The Broader Pattern

This policy exemplifies a recurring feature of UK institutional decline: the gap between claimed capability and actual delivery.

Transport policy encourages cycling as an alternative to car use. Stations build bike parking infrastructure. Government communications promote sustainable transport choices. Then the police force responsible for transport hubs announces it will not investigate most bicycle thefts.

The result is policy contradiction at the implementation level. Citizens are encouraged to cycle to stations while simultaneously informed that their bicycles will not be protected once they arrive.

This mirrors patterns visible across other public services. Infrastructure is built and promoted while the institutional capacity to make it function is quietly withdrawn. The appearance of service provision continues while actual provision deteriorates.

Compare this to enforcement in the Netherlands, where nearly half of station trips are by bicycle. That outcome requires not just infrastructure but functional enforcement. The UK has invested in the former while abandoning the latter.

What This Means For Citizens

If you cycle to a railway station in Britain, your bicycle is now effectively unprotected by law. The “secure” parking you may pay for provides no meaningful security. The CCTV cameras are decorative. The police will not investigate the theft.

This matters beyond the immediate cost of stolen bicycles. It represents the breakdown of a basic social contract: that property crimes will be investigated and prosecuted. When institutions openly declare they will not enforce laws in entire categories of crime, the concept of rule of law begins to erode at the edges.

The British Transport Police justify this by claiming they must focus on “crimes which cause the most harm.” But theft of personal property does cause harm, both financially and in lost trust in institutions. More fundamentally, when police forces begin publicly announcing which crimes they will not investigate, they are admitting they lack the capacity to perform their core function.

The Institutional Admission

The most revealing aspect of this policy is what it admits about British Transport Police capability. The force is openly stating it cannot investigate property crime at transport hubs while maintaining visible patrols.

This is presented as a choice about priorities. It is actually an admission of institutional failure. A functional police force would not need to choose between investigating thefts and maintaining station presence. The choice itself reveals inadequate resources, staffing, or operational effectiveness.

The suggestion by victims that British Transport Police should hand responsibility to local forces acknowledges the obvious: BTP can no longer perform its designated role. But this merely relocates the problem rather than solving it, as local forces face similar capacity constraints.

What The Data Shows

The policy includes specific parameters that reveal its purpose. Bikes under £200 are excluded. Two-hour windows eliminate most commuter thefts. Train thefts require knowing the exact carriage. These are not investigative standards, they are filters designed to reduce reported crime from the workload.

The British Transport Police claim these crimes provide “valuable intelligence” for directing patrols. But intelligence without enforcement is simply documentation of decline. Recording crimes you will not investigate generates statistics, not deterrence.

The force notes these are crimes “unlikely to ever be solved.” This may be accurate, but it prompts the obvious question: why are they unlikely to be solved? Is it because investigation is genuinely impossible, or because insufficient resources and capability have been allocated?

The Green Transport Contradiction

This policy directly contradicts stated government objectives around sustainable transport. If citizens cannot safely leave bicycles at stations, they will use cars instead. The London Cycling Campaign notes that theft drives people away from cycling entirely.

Investment in cycling infrastructure becomes wasted expenditure if the infrastructure cannot be used safely. Building bike parks while announcing bikes will not be protected is policy incoherence at the implementation stage.

This pattern repeats across environmental initiatives. Goals are announced, infrastructure is partially built, and then the operational capacity to make it function is withdrawn due to budget or staffing constraints. The result is failed delivery despite stated commitments.

What This Reveals About UK Governance

The bike theft policy demonstrates a now-familiar pattern in British institutional function. Services are reduced or withdrawn, but the reduction is presented as rational prioritisation rather than capacity failure.

British Transport Police cannot investigate property crime at stations while maintaining other operations. Rather than acknowledge this as an institutional problem requiring remedy, the policy simply redefines most bike theft as non-investigable. The failure is transformed into policy.

This approach allows institutions to claim they are focusing on priorities rather than admitting they cannot deliver basic functions. It shifts responsibility from the institution to the victim, whose property was left “too long” to warrant investigation.

The pattern is now visible across multiple public services. Waiting lists are redefined as acceptable. Infrastructure projects are delayed indefinitely. Service standards are quietly reduced. In each case, institutional failure is reframed as policy choice.

The Cost of Enforcement Failure

When police forces announce they will not investigate entire categories of crime, several outcomes follow. First, crime in those categories increases as perpetrators recognise the lack of consequences. Second, citizens lose faith in institutions meant to protect them. Third, social norms around property and law begin to shift.

The British Transport Police policy communicates clearly to both criminals and citizens: bike theft at stations carries no meaningful risk. This creates exactly the incentive structure that encourages more theft, requiring citizens to make different transport choices to protect their property.

The cost is not just stolen bicycles. It is the erosion of institutional legitimacy that occurs when organisations openly state they will not perform their designated functions. Each such admission reduces public confidence in governance effectiveness.

The Bigger Picture

Britain has invested billions in transport infrastructure, cycling initiatives, and station improvements. Those investments require institutional capacity to function. When that capacity fails, the infrastructure becomes worthless.

This is not about partisan politics. It is about basic institutional competence. A police force that cannot investigate property crime while maintaining patrols is a police force that lacks adequate resources, staffing, or effectiveness.

The solution is not to decriminalise theft through non-investigation. The solution is to provide sufficient capacity for institutions to perform their core functions. That requires either increased resources or fundamental restructuring of how services are delivered.

Instead, Britain continues to build infrastructure it cannot adequately protect, announce initiatives it cannot fully implement, and present institutional failure as policy choice. The bike theft policy is simply the latest visible example of a broader pattern of decline.

Commentary based on Bike thefts at stations 'decriminalised' by Tom Edwards on BBC News.