Copenhagen Officials Reshape Whitehall's Asylum Lock

Home Office eyes temporary stays and family curbs as Channel arrivals hit records

Labour imports Denmark's tough immigration model amid uncontrolled borders, exposing cross-party failures in enforcement and integration that strain UK institutions.

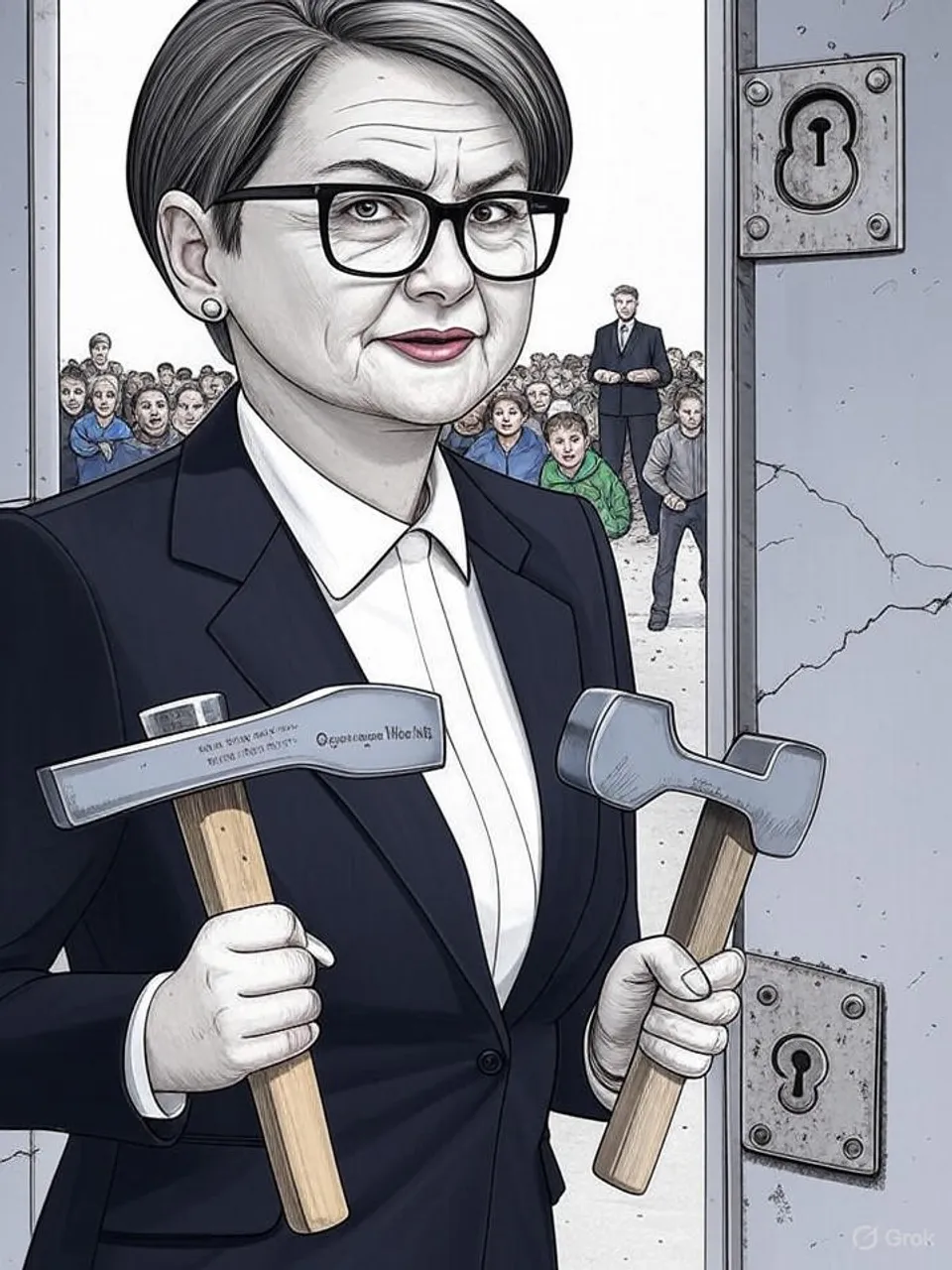

Shabana Mahmood dispatches Home Office officials to Copenhagen, seeking blueprints for a tougher asylum regime as small boat crossings persist unchecked. Labour pledges border control after inheriting a system that processed 67,000 asylum claims last year, yet net migration reached 685,000 in 2023 under the prior government. This foreign scouting exposes a core dysfunction: decades of domestic policy failures now force reliance on Denmark’s model.

Denmark’s system grants temporary protection to most refugees, revocable once home countries stabilize. Successful claimants face extended waits for settlement, mandatory full-time work, and language proficiency tests. Family reunions demand both partners over 24, no recent benefits claims, financial guarantees, and exclusion from “parallel society” estates—areas with over 50% non-Western residents.

These measures slashed Denmark’s successful asylum claims to a 40-year low, barring the 2020 pandemic dip. Officials there expelled more foreign criminals and offered up to £24,000 incentives for voluntary returns, including child education support. Integration demands participation, with non-contributors facing deportation.

Mahmood aims to curb UK incentives like family reunions, suspended since September pending restrictive rules. She eyes easier expulsions and reduced draws for migrants, echoing Denmark’s temporary stays. Yet the UK skips financial return incentives, limiting the import to selective tightenings.

Denmark’s Social Democrats drove these changes from 2015, neutralizing right-wing populism and securing space for green and welfare policies. A smaller nation of 5.9 million, it lacks the UK’s Channel crossings or English-language pull. Danish integration targets a homogeneous society; Britain’s diverse 67 million strains under similar rules without adaptation.

Labour’s internal rift mirrors this mismatch. Left-wing MPs label the Danish approach “hardcore,” fearing far-right echoes, while mainstream figures resist off-record. Clive Lewis warns against outflanking Reform UK, highlighting party fractures that dilute policy execution.

Past governments promised control too. The Conservatives’ 2010-2024 tenure saw net migration climb from 250,000 to 685,000, Rwanda schemes falter in courts, and enforcement budgets lag. Labour’s 1997-2010 era opened EU free movement, adding millions without infrastructure scaling.

This pattern spans parties: rhetoric surges, arrivals continue. The Home Office processed 29,000 small boat arrivals in 2023, up from 2022, amid ECHR constraints both nations navigate. Denmark reviews ECHR tweaks; the UK debates exit under Tory leadership, but Labour stays committed without resolution.

Expulsion gaps persist. Denmark ejects criminals swiftly; the UK released a migrant sex offender erroneously in Wandsworth last year, delaying reports. Overcrowding freed 262 prisoners wrongly in England and Wales recently, blending justice and immigration breakdowns.

Mahmood’s “whatever it takes” vow at conference rings hollow against these realities. Officials scrutinize Copenhagen, but systemic voids—underfunded borders, court backlogs, local integration failures—undermine transplants. Denmark’s scale works; Britain’s amplifies flaws.

The exercise reveals institutional pathology: power brokers borrow abroad to mask domestic inertia, prioritizing political optics over enforceable reform. Ordinary citizens face strained housing, services, and cohesion as arrivals outpace controls. This Danish detour underscores a deeper truth—UK governance reacts to crises it perpetually creates, eroding sovereignty one unadapted policy at a time.

Commentary based on UK seeks inspiration from Denmark to shake up immigration system at BBC News.