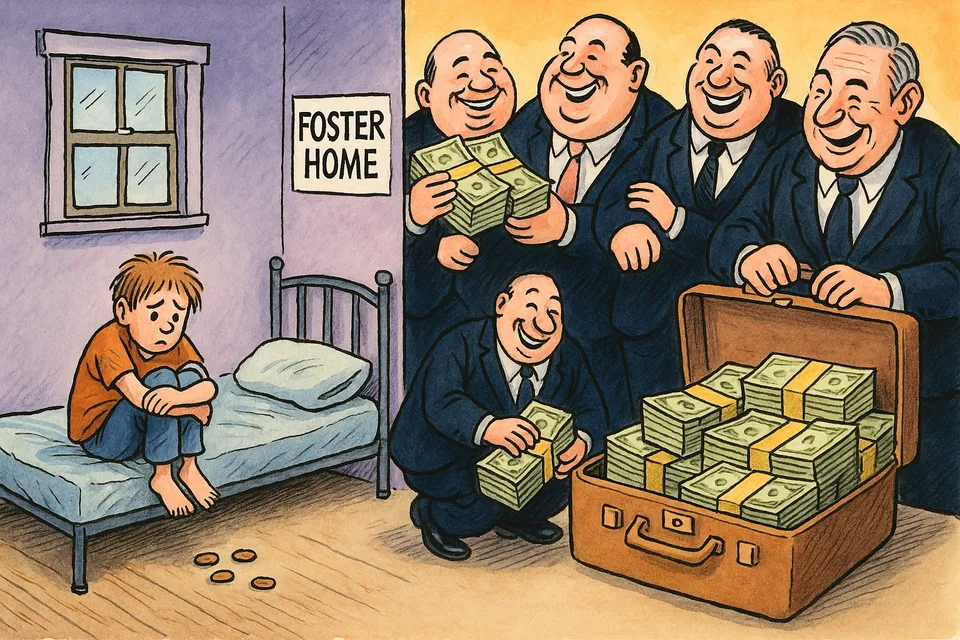

The Foster Care Gold Rush: How Private Equity Profits from Britain's Most Vulnerable Children

Children as Commodities: The Dark Side of Foster Care Privatization

While politicians debate child welfare reforms, private equity firms have quietly transformed foster care into a £104 million profit machine. Almost a quarter of England's foster placements now exist primarily to generate returns for investment funds, with vulnerable children reduced to revenue units in sophisticated financial models.

Commentary Based On

The Guardian

Nearly a quarter of foster places in England provided by private equity-backed firms

What they claim: Private fostering agencies are investing in training and support to deliver better outcomes for vulnerable children, with National Fostering Group boasting of creating “£30m in social value” through their services.

What is happening: These same agencies extract £104 million in profits by charging councils £1,000 per week per child while paying foster carers just £300, leaving carers earning 80p per hour and relying on universal credit while private equity owners accumulate millions from public budgets meant for child welfare.

The privatization of foster care represents one of Britain’s most cynical institutional failures. Four private equity-backed companies now control 23% of all foster placements in England - 16,365 children whose care generates extraordinary profits. National Fostering Group, the largest operator, extracted £104 million in underlying profits in 2023 with a 21% margin. Foster Care Associates generated £49.1 million.

These profits flow from a simple arbitrage: councils pay independent fostering agencies up to £1,000 per week per child, while foster carers receive around £300. The £700 difference funds not just operational costs but substantial returns to private equity owners. One agency makes an estimated £1,500 profit per placement annually.

Meanwhile, the actual carers - those providing round-the-clock care for traumatized children - calculate their earnings at 80p per hour. Many rely on universal credit to survive while caring for society’s most vulnerable young people.

The Commodification Machine

What we’re witnessing is the systematic commodification of child welfare. Private equity firms have identified foster care as an ideal investment opportunity: guaranteed demand from cash-strapped councils, minimal capital requirements, and the ability to extract value through operational “efficiencies” that ultimately mean paying carers less while charging councils more.

The business model is brutally simple. Buy up smaller fostering agencies, consolidate operations, leverage market position to raise prices to desperate councils, minimize payments to carers, extract maximum profit. Children become units of production in spreadsheets optimized for returns.

This isn’t a market failure - it’s the market working exactly as designed when applied to essential public services. Local authorities, hollowed out by austerity and lacking capacity to recruit foster carers directly, have no choice but to pay whatever private agencies demand. The Competition and Markets Authority found operating costs are £8,400 higher per child through private agencies than council provision.

Institutional Surrender

The privatization of foster care represents a complete institutional surrender. Councils have essentially admitted they cannot perform one of their most fundamental duties - caring for vulnerable children - and have handed responsibility to profit-maximizing entities.

Robin Findlay of the National Union of Professional Foster Carers identifies the core dysfunction: “You’ve got to ask: why do these agencies exist? They exist because local authorities have failed.” But rather than rebuild internal capacity, councils continue outsourcing at escalating costs, creating what one anonymous foster carer describes as “rampant profiteering” that pushes many authorities toward bankruptcy.

The Department for Education’s response - promising to “crack down on care providers making excessive profit” through new legislation - fundamentally misunderstands the problem. You cannot regulate away the contradictions of running essential services for private profit. The incentives remain unchanged: maximize extraction from public budgets while minimizing costs.

The Human Cost of Financial Engineering

Behind the profit margins lie real consequences. Foster carers struggle financially despite providing 24/7 care for traumatized children. High turnover follows inevitably - who can sustain such work at 80p per hour? Children face instability as carers leave the profession, agencies consolidate, and placement availability shrinks.

The four largest providers claim high regulatory ratings and investment in training. National Fostering Group boasts of delivering “200,000 hours of training” creating “£30m in social value.” But this corporate speak cannot obscure the fundamental reality: they exist to generate returns for investors, not serve children’s needs.

As these firms grow larger through acquisition, they become “too big to fail” - if one collapsed, thousands of children would need immediate rehousing. This gives them even greater leverage over councils already struggling with budgets devastated by fourteen years of austerity.

Britain’s Caring Deficit

The foster care crisis exemplifies Britain’s broader institutional decay. Essential services that should embody social solidarity - caring for vulnerable children - have been financialized and optimized for profit extraction. Those who do the actual caring work are impoverished while distant investors accumulate millions.

This isn’t a policy failure that better regulation can fix. It’s the logical endpoint of treating public services as investment opportunities. Every pound extracted as profit is a pound not spent on supporting foster carers or improving children’s outcomes. Every private equity acquisition further embeds market logic into domains that should operate on entirely different principles.

Local authorities know this system is broken. Foster carers know it’s exploitative. The companies themselves know their profits depend on maintaining dysfunction - if councils could recruit carers directly and pay them properly, the intermediary profits would vanish. Yet the system persists because decades of hollowing out state capacity has left no immediate alternative.

The Permanent Crisis

What makes this particularly revealing about Britain’s decline is how permanent the crisis has become. The privatization of foster care began accelerating after 2010’s austerity measures. Fifteen years later, the problems have only intensified. Costs spiral, carers leave, children suffer, profits grow. No party offers meaningful solutions because addressing root causes would require rebuilding state capacity and challenging embedded private interests.

Instead, we get rhetorical commitments to “crack down” on “excessive” profits while maintaining the fundamental structure that generates those profits. The same pattern repeats across public services: water, energy, transport, social care. Essential infrastructure becomes a vehicle for rent extraction while service quality deteriorates and costs escalate.

The foster care system reveals British governance at its most cynical - creating markets in human misery, enabling sophisticated financial engineering around childhood trauma, impoverishing those who provide care while enriching those who financialize it. This is what institutional decline looks like: not dramatic collapse but the slow commodification of everything, including childhood vulnerability itself.

Commentary based on Nearly a quarter of foster places in England provided by private equity-backed firms by Jessica Murray and Aamna Mohdin on The Guardian.