The NHS Exodus: When Poland Outperforms Britain

British patients now flee to Eastern Europe for procedures their own system can't provide

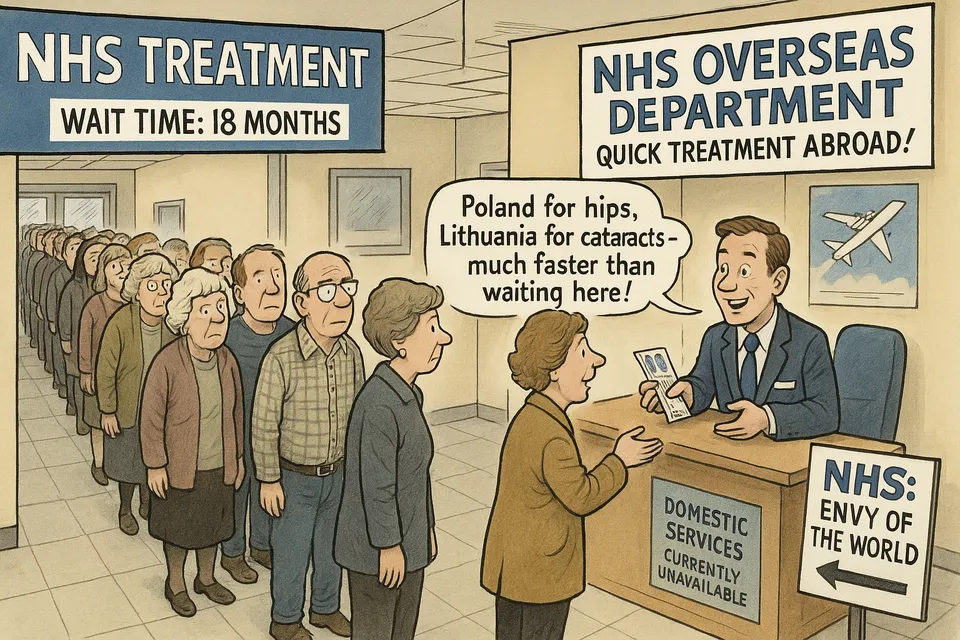

While politicians continue proclaiming the NHS as the "envy of the world," British patients are now fleeing to Poland, Lithuania, and the Czech Republic for basic medical care their own healthcare system cannot provide. This isn't medical tourism—it's medical refuge, funded by a health service so broken that paying foreign hospitals has become cheaper than fixing domestic capacity.

A 42% surge in patients sent abroad in just two years, with NHS approval rates for overseas treatment nearly doubling from 21% to 37%. When a healthcare system starts systematically exporting its patients to countries it once considered medically inferior, something fundamental has failed.

What they claim: The NHS remains the “envy of the world” and delivers world-class healthcare free at the point of use to all British citizens. What actually happened: British patients now queue for treatment in Polish hospitals because their own healthcare system has become so dysfunctional that exporting the sick abroad is cheaper than providing domestic care.

The Key Facts

The data reveals the scale of systemic breakdown. Over three years, 352 British patients have been dispatched across Europe at a cost of £4.32 million—money that could have funded domestic capacity but instead subsidises foreign healthcare systems. Poland now treats more NHS patients than many British hospitals, with 72 procedures performed there between 2022-25.

The waiting list crisis has reached a perverse milestone: 1.4 million people awaiting basic gynaecological or orthopaedic procedures, with 43,000 waiting over a year since diagnosis. For hip replacements and cataract operations—routine procedures any functional healthcare system should manage—British patients must now travel hundreds of miles to former Eastern Bloc countries.

Ireland, despite its smaller population, extracted £3.15 million from the NHS for treating British patients—more than any other country. This represents a complete reversal of historical medical flows, where patients once travelled to Britain for superior care.

NHS Decline

This medical exodus exemplifies three key patterns of UK institutional decline:

First, the collapse of basic competence. Hip replacements and cataract operations are not cutting-edge procedures. They represent routine healthcare delivery that any developed nation should manage domestically. When Britain cannot perform these basics, it signals fundamental institutional failure rather than temporary strain.

Second, the normalisation of dysfunction. Officials present overseas treatment as innovative policy rather than admission of systemic collapse. The fact that only 37% of applications for foreign treatment are approved suggests thousands more would flee if bureaucratic barriers were removed. The NHS has become a rationing system masquerading as a healthcare service.

Third, the creation of new inequalities within alleged universality. The overseas scheme requires patients to fund their own travel and accommodation—effectively creating a two-tier system where those with means can escape to functioning healthcare while others endure indefinite waits. This undermines the foundational principle of “free at the point of use” while maintaining the fiction of universal provision.

Institutional Inversion

The medical refugee crisis follows a familiar pattern across UK institutions: progressive degradation hidden behind unchanged rhetoric. For decades, politicians have proclaimed NHS superiority while measurable outcomes deteriorated. The system now exhibits characteristics typically associated with failing states—the inability to provide basic services to citizens.

This parallels broader institutional inversions across British governance. The education system that once attracted international students now struggles with basic literacy. The justice system that exported legal frameworks globally now cannot process cases within reasonable timeframes. The financial services sector that dominated global markets now faces systematic exodus to European competitors.

The overseas treatment scheme represents the logical endpoint of institutional denial—when domestic failure becomes undeniable, export the problem rather than address the causes.

Reality Check

Wes Streeting’s response exemplifies the gap between political rhetoric and institutional reality. He promises to “catapult the NHS into the 21st century” while presiding over a system that cannot perform 20th-century procedures domestically. His claim of delivering “3.6 million more appointments” while waiting lists remain at crisis levels reveals the statistical manipulation that obscures institutional failure.

The “undue delay” criterion for overseas treatment formally acknowledges what the system won’t publicly admit—that NHS waiting times have become medically dangerous. When bureaucrats determine that British hospitals represent “undue delay” compared to Polish alternatives, they’re conceding systemic breakdown while maintaining the pretence of world-class healthcare.

The geographical pattern reveals the extent of decline. Patients travel to countries that, within living memory, were considered medically underdeveloped compared to Britain. Poland, Lithuania, and the Czech Republic now provide superior access to basic procedures than the NHS—a reversal that would have been unthinkable thirty years ago.

This medical exodus represents more than healthcare failure—it demonstrates the hollowing out of British institutional capacity. The NHS was once a symbol of post-war British competence and social solidarity. Its degradation into a medical export system reveals how institutional decay spreads throughout the governance structure.

The European countries now treating British patients didn’t achieve superior outcomes through revolutionary innovation—they maintained basic healthcare functionality while Britain allowed its system to deteriorate through decades of political short-termism and managerial dysfunction.

The £4.32 million spent on overseas treatment represents diverted resources that could have built domestic capacity. Instead, it subsidises foreign healthcare systems while British infrastructure continues degrading. This creates a perverse incentive structure where institutional failure becomes self-perpetuating—the more the system fails, the more resources flow abroad rather than toward domestic solutions.

Let’s Be Honest

The NHS’s transformation into a medical export industry is not a sign of progress but a symptom of institutional rot. The fact that British patients now queue for treatment in countries that once relied on British medical expertise is a profound indictment of how far the NHS has fallen.

The medical refugee crisis exposes the fundamental dishonesty underlying British political discourse. For years, politicians across parties have claimed to “protect” and “reform” the NHS while presiding over its systematic deterioration. The overseas treatment scheme provides convenient cover—allowing officials to claim they’re “delivering care” while avoiding acknowledgement of domestic institutional collapse.

British patients queuing in Polish hospitals represent the visible manifestation of invisible governance failure. They are the human cost of decades of institutional drift, political cowardice, and administrative incompetence disguised as policy innovation.

When Britain’s healthcare system cannot perform routine procedures that former Soviet satellites manage efficiently, the question isn’t whether the NHS requires reform—it’s whether British institutions retain the capacity for genuine renewal rather than continued managed decline dressed as modernisation.

The “envy of the world” has become a medical export industry. That transformation didn’t happen overnight—it represents the accumulated consequence of treating institutional decay as acceptable while maintaining rhetorical commitments to excellence. The patients boarding flights to Warsaw for hip replacements embody the distance between British political rhetoric and British administrative reality.

This is what institutional decline looks like when it can no longer be hidden behind statistics and spin—citizens fleeing abroad for services their own country once provided as a matter of routine competence.

Commentary based on NHS sends patients abroad after waiting lists hit record high by Rosie Taylor on Telegraph.