The UK's Surveillance State: When "World Leader" Means Showing Dictators How It's Done

The UK is no longer an "Open" country for free expression

While British politicians still invoke Churchill and speak of defending democracy worldwide, their own freedom rankings have quietly slipped below Romania and Nigeria. The UK has lost its status as an "Open" society for free expression—a designation it held since measurements began—and now pioneers surveillance techniques that authoritarian regimes watch with interest.

Article 19’s latest Global Expression Report presents the trajectory with clinical precision. From a steady score of 88 between 2000 and 2013, the UK has fallen to 79 in 2024. This isn’t a blip or statistical anomaly. It’s a decade-long descent that accelerated after 2019, dropping six points in just five years.

The organization measures 25 indicators including media freedom, internet censorship, academic independence, and citizens’ ability to criticize power. Countries scoring 80-100 are classified as “Open.” The UK now sits at 79, joining the “Less Restricted” category alongside Colombia, Nigeria, Romania, and South Africa.

For a nation that markets itself as the “mother of parliaments” and birthplace of liberal democracy, this represents more than a statistical embarrassment. It’s measurable proof that British institutions no longer function as advertised.

From Democratic Pioneer to Surveillance Innovator

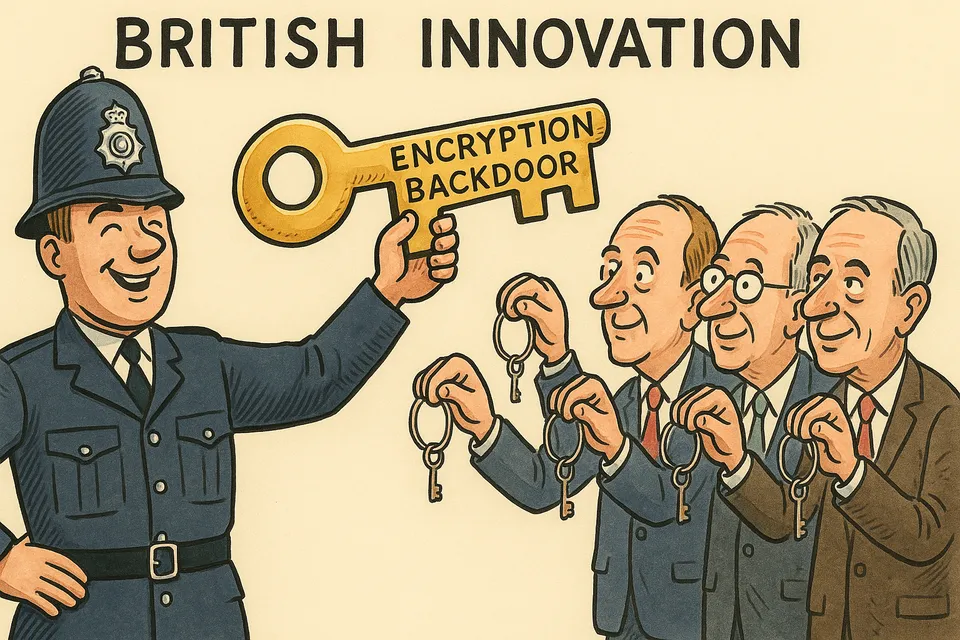

The most revealing aspect isn’t the decline itself but what caused it. Under the Investigatory Powers Act—dubbed the “Snooper’s Charter”—the UK government issued a Technical Capability Notice to Apple, demanding the company reengineer its systems to enable future government access to encrypted data.

This goes beyond traditional surveillance warrants. The government isn’t asking for specific information about individuals under investigation. It’s compelling Apple to break encryption preemptively, creating permanent infrastructure for mass surveillance whether or not it’s ever officially activated.

Apple’s own submission to Parliament warned that end-to-end encryption protects “journalists, human-rights activists and diplomats who may be targeted by malicious actors.” The company now faces the choice of complying, withdrawing services from the UK market, or fighting lengthy court battles while being legally required to begin compliance during appeals.

The Authoritarian Playbook, British Edition

David Diaz-Jogeix of Article 19 notes the “irony” of Western democracies adopting repressive policies. But the real irony runs deeper: the UK isn’t just copying authoritarian methods—it’s innovating them.

China, Russia, and Iran traditionally relied on crude censorship and visible repression. The UK demonstrates a more sophisticated approach: maintain democratic language while building surveillance architecture that would make the Stasi envious. Then wrap it in legal procedures and technical jargon so complex that most citizens won’t understand what’s happening until it’s operational.

Once Apple creates a “backdoor” for UK authorities, every authoritarian regime gains a powerful argument. If Britain can demand access, why not Turkey, Iran, or China? The technical capability, once built, becomes a global tool. The UK hasn’t just weakened its own citizens’ privacy—it’s provided the blueprint for worldwide surveillance expansion.

The Pattern of Institutional Decay

This isn’t an isolated incident but part of systematic institutional failure:

Political Theatre vs Reality: Ministers speak of “British values” and “defending democracy” while actively dismantling the foundations of free expression. The gap between rhetoric and action has become a chasm.

Bureaucratic Mission Creep: Powers granted for “terrorism” and “serious crime” inevitably expand. The same pattern repeats: emergency measures become permanent, limited powers become universal, oversight becomes rubber-stamping.

Cross-Party Consensus: These surveillance powers expanded under both Conservative and Labour governments. The problem isn’t partisan—it’s institutional. The machinery of state surveillance grows regardless of who claims to be in charge.

International Reputation: The UK trades on historical reputation while current reality diverges. British officials lecture other nations on human rights while building surveillance systems those nations eagerly study.

What This Actually Means

For ordinary citizens, the implications extend beyond abstract rankings:

Digital Privacy: Every message, photo, and document stored on devices or in the cloud becomes potentially accessible. Not just to UK authorities, but eventually to any government that successfully demands equal treatment.

Journalistic Sources: Whistleblowers and sources can no longer trust encrypted communications. This chills investigative journalism and accountability reporting—precisely the kind that exposes institutional failures.

Professional Communications: Lawyers, doctors, therapists, and others who rely on confidential communications face ethical dilemmas. How do you maintain professional confidentiality when the government has preemptively broken encryption?

Economic Competitiveness: Tech companies may withdraw services or avoid UK markets. Financial services, already nervous post-Brexit, face additional concerns about client confidentiality. The UK positions itself as a difficult place to do secure business.

Boiling the Frog

The eight-point drop over a decade seems modest—less than one point per year. This gradual pace explains why there’s no public outcry. British citizens, like the proverbial frog in slowly heating water, don’t notice the temperature rising until it’s too late.

Each year brings small erosions: a new surveillance power here, a restriction on protest there, another exception to privacy rights. Individually, they seem reasonable. Collectively, they transform an open society into something resembling a well-mannered police state.

The government counts on this gradualism. By the time citizens realize what’s happened, the infrastructure is built, the legal frameworks established, and reversal becomes nearly impossible. Who will vote to “weaken security” or “help criminals communicate secretly”? The political framing ensures the ratchet only turns one way.

Freddie Attenborough observes that Britain can now claim to be a “world leader” in showing authoritarians the way forward. This isn’t hyperbole. When Western democracies pioneer surveillance techniques, they provide cover for dictatorships worldwide.

The UK’s approach offers several advantages over traditional authoritarian methods:

- Legal frameworks that provide procedural legitimacy

- Technical sophistication that makes resistance difficult

- Corporate compliance enforced through law rather than crude threats

- Public acquiescence achieved through security theater rather than visible oppression

This represents Britain’s new export economy: not manufacturing or services, but surveillance innovation. The techniques developed in Westminster will be studied in Beijing, Moscow, and Tehran. The UK has become a laboratory for sophisticated authoritarianism.

The Uncomfortable Truth

The UK’s loss of “Open” status isn’t a temporary setback or technical classification issue. It’s the measurable result of deliberate choices by successive governments, enabled by institutional failures and public indifference.

British citizens now live in a country that ranks below nations they’re taught to view as less developed or less democratic. This isn’t because those nations improved—it’s because the UK declined. The direction of travel is clear: away from open society principles and toward expanded state surveillance.

The government will dispute these rankings, cite security needs, and promise safeguards. They’ll use the language of democracy while building the architecture of control. They’ll insist Britain remains a beacon of freedom while extinguishing the light.

But data doesn’t lie. The UK is no longer an “Open” country for free expression. It’s a “Less Restricted” one—a euphemism that disguises how far standards have fallen. And based on current trajectory, even that modest classification may prove optimistic.

The decline continues. Now it’s just officially measured.

Commentary based on The UK is no longer an “open” country for free expression? by Freddie Attenborough on The Critic.