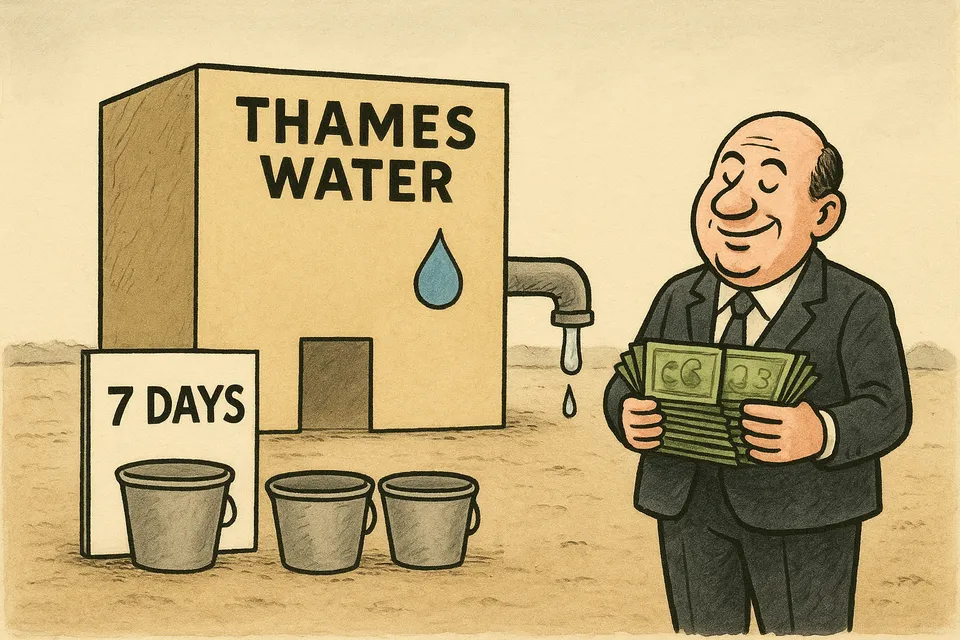

The £518 Million Mirage: How Thames Water Turned London's Water Security Into a Financial Extraction Scheme

Desalination Disaster and the Illusion of Infrastructure

Thames Water's £518 million desalination plant, built to secure London's water supply, has produced a mere seven days' worth of water over 15 years. This exposé reveals how the plant, plagued by operational failures and exorbitant costs, serves more as a financial asset for debt accumulation than a functional piece of infrastructure. As the company seeks another £535 million for a new project, the story highlights the systemic issues in Britain's privatised water industry, where public service is secondary to wealth extraction.

Commentary Based On

The Guardian

£500m Thames Water desalination plant has provided just seven days’ water over 15 years

Thames Water spent half a billion pounds on a desalination plant that has produced seven days of London’s water supply over 15 years. While the company now pleads for another £535 million from customers for yet another drought-resilience scheme, the Beckton facility stands as a monument to institutionalised incompetence—a machine designed to extract wealth rather than water.

Key Facts

The numbers tell a story of systematic failure that no amount of corporate messaging can obscure:

The Thames Gateway desalination plant has cost £518 million since 2010—£270 million to build, £200 million in debt interest, £45 million in idle maintenance, and £3 million to operate. For this astronomical sum, London received 7.2 billion litres of water. That’s seven days of typical demand spread across fifteen years.

Each litre produced cost 7 pence—28 times what customers normally pay. The plant has run exactly five times. Chemical leaks have forced workers into protective suits. System failures created “health and safety issues” that prevented operation. The facility is currently offline for “reservoir safety related works.”

Meanwhile, Thames Water loses 570.4 million litres every single day through leaks—roughly 80 times what the desalination plant produces in an entire year.

Critical Analysis

This isn’t infrastructure failure. It’s infrastructure as financial instrument. The desalination plant exists not to provide water security but to create an asset against which Thames Water can borrow. The £270 million construction cost became collateral for debt that has now accumulated £200 million in interest alone—money that went to financial institutions, not water provision.

The plant’s non-functionality is almost beside the point. Its primary purpose was always financial engineering, not civil engineering. Thames Water created a half-billion pound asset that sits idle while the company extracts payments from customers for its theoretical existence.

Chris Weston, Thames Water’s CEO, admitted to MP Munira Wilson that the plant “doesn’t work the way we expected it to.” This understates reality with corporate elegance. The plant doesn’t work at all in any meaningful sense. It’s a financial monument to regulatory capture—approved, funded, and maintained despite fundamental operational failure.

The Pattern

The Beckton debacle follows a familiar template in Britain’s privatised water industry: Promise essential infrastructure to justify price increases. Build expensive facilities that barely function. Use these assets as collateral for debt. Extract interest payments while infrastructure decays. Propose new projects to solve problems the previous projects were meant to address.

Thames Water now proposes the Teddington Direct River Abstraction scheme at up to £535 million—funded, naturally, by customers who already paid for the non-functional desalination plant. The TDRA would pump clean Thames water to north London reservoirs and replace it with treated sewage effluent. The company insists this treated effluent is “clean recycled water” while simultaneously requiring extensive regulatory approval to prove it’s safe.

The senior water industry figure quoted cuts through corporate euphemism: “Father Thames is going to get hit because you’re taking clean water out and you’re putting dirtier water back in.”

The Reality Check

Britain faces a water crisis not because of climate or geography but because of institutional design. The privatised water system incentivises debt accumulation over infrastructure maintenance, financial engineering over actual engineering, and wealth extraction over public service.

Thames Water’s business model depends on creating expensive assets that justify borrowing, which generates returns for shareholders and bondholders while leaving customers with dysfunctional infrastructure and higher bills. The desalination plant’s failure isn’t a bug in this system—it’s a feature.

The regulatory framework that approved a £270 million project without performance guarantees, that allows it to sit idle while accumulating hundreds of millions in costs, and that now considers approving another half-billion pound scheme from the same company, reveals complete institutional capture. Ofwat, the Environment Agency, and Defra have become enablers rather than regulators.

The Bigger Picture

The Beckton desalination plant embodies British institutional decline in microcosm. A wealthy nation cannot provide basic water security to its capital because the system is designed for financial extraction, not public service. The infrastructure exists, the money was spent, but the water doesn’t flow.

England faces a predicted 5 billion litre daily water shortage by 2055, with half that deficit in the southeast. The response isn’t competent planning or serious infrastructure investment but schemes like Beckton—expensive failures that generate debt, not solutions.

When Thames Water’s spokesperson claims the company needs both the non-functional desalination plant and the proposed TDRA scheme “along with our significant investment in leaks,” they reveal the truth: customers will pay for everything while nothing actually improves. The leaks will continue at 570 million litres daily. The desalination plant will remain largely idle. The new scheme, if built, will likely follow the same trajectory.

This is how modern Britain works. Not through conspiracy or incompetence alone, but through systems deliberately designed to extract value while delivering failure. The Beckton plant isn’t broken—it’s working exactly as the financial system intended. The water it was supposed to provide was always secondary to the debt it was designed to generate.

Seven days of water for £518 million. In any functional society, this would trigger immediate investigation, accountability, and fundamental reform. In declining Britain, it triggers a request for another £535 million for the next inevitable failure.

The taps still run, for now. But they run on debt, not desalination. And when that debt finally overwhelms the system, Londoners will discover that all those billions bought them neither infrastructure nor resilience—just seven days of water and a lifetime of payments for promises that were never meant to be kept.

Commentary based on £500m Thames Water desalination plant has provided just seven days’ water over 15 years by Rachel Salvidge on The Guardian.