When Good Numbers Hide Bad News: The IMF's Uncomfortable Truth About Britain

Growth, Inflation, and Institutional Failure

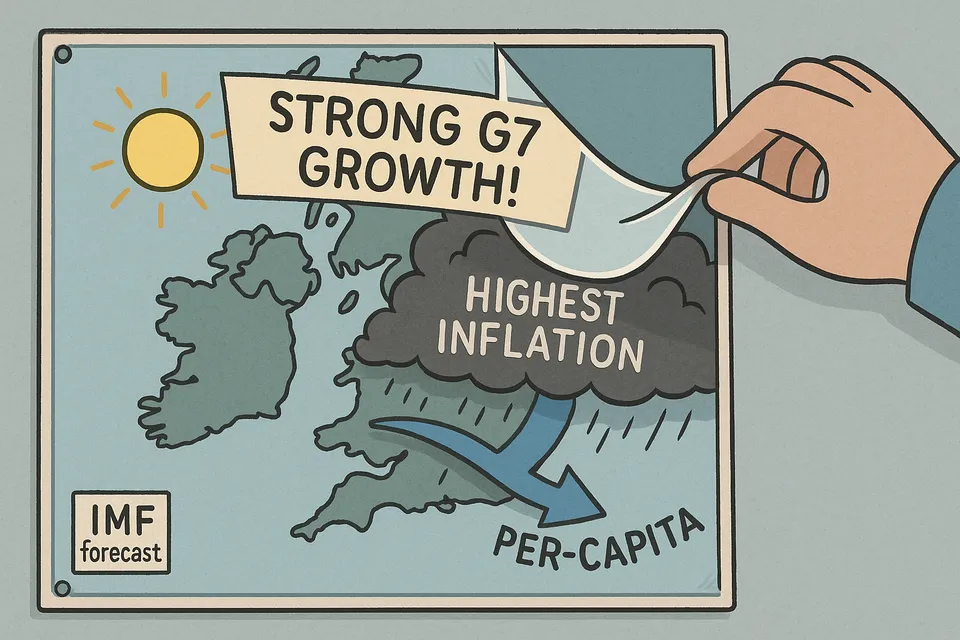

The IMF forecasts Britain will have the second-strongest economic growth in the G7 this year. But it also predicts Britain will have the highest inflation and the weakest per-capita growth next year. This is not a contradiction. This is a symptom of deeper institutional problems.

The International Monetary Fund delivered its latest economic outlook this week, and somewhere in Westminster a civil servant has already circled the figure that matters: Britain forecast to have the second-strongest economic growth in the G7 this year, behind only the United States.

This is the number that will feature in ministerial statements, Treasury briefings, and optimistic social media posts. It will be presented as evidence that the government’s economic strategy is working.

The IMF report contains other numbers. These ones will not feature in many press releases.

What The Data Actually Shows

Britain has the highest inflation rate in the industrialised world. Not just high. The highest in the G7, both this year and next.

While politicians will tout overall GDP growth figures, the measure that actually matters to citizens tells a different story. GDP per capita, which accounts for population growth, reveals Britain is forecast to have the weakest growth in the G7 next year at just 0.5 percent.

Think about that. Your country can grow its total economic output while the average person sees virtually no improvement in their economic position. This is the statistical sleight of hand that allows governments to claim success while living standards stagnate.

The IMF report presents these facts without drama. Britain is simultaneously experiencing relatively strong headline growth and the worst inflation among its peers. This is not a contradiction. This is a symptom.

The Question Nobody Wants To Answer

Why is Britain such an outlier on inflation?

According to Sky News, this is a question both Chancellor Rachel Reeves and Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey will have to explain at this week’s IMF meetings in Washington. Whether they will provide honest answers is another matter entirely.

The pattern is familiar. Britain enters each economic cycle promising competent management. Britain exits each cycle with outcomes worse than comparable nations. The personnel change. The parties change. The excuses change. The underperformance remains constant.

High inflation is not an abstract economic indicator. It is the mechanism by which wealth transfers from those who earn it to those who own assets. It is how savings evaporate and wages lose purchasing power. It is the difference between planning for the future and surviving the present.

The Institutional Deficit

The IMF upgraded its global growth forecast from 2.8 percent to 3.2 percent. This was not because the Fund suddenly became optimistic about trade policy. It was because Donald Trump’s tariff impact proved smaller than initially feared, and because “unexpected resilience” appeared in economic activity.

Britain managed to be an inflation outlier even as global economic conditions improved beyond expectations.

This is worth examining. When global conditions worsen, Britain suffers along with everyone else. When global conditions improve, Britain improves less than everyone else. The common factor in both scenarios is Britain’s institutional performance.

The IMF is diplomatic in its language. It notes that factors providing current economic relief are “temporary” rather than reflecting “underlying strength in economic fundamentals.” Translation: the foundations remain weak.

What Gets Measured, What Gets Ignored

The Treasury will focus on that second-place growth ranking because it is technically accurate and politically useful. This is how institutional decline operates in practice. Not through obvious failure, but through selective presentation of partial success.

GDP per capita growth of 0.5 percent next year means the average British person’s economic situation will barely move. In a country already experiencing sustained living standards pressure, infrastructure decay, and public service deterioration, this is not stability. This is managed decline.

The inflation figures reveal something more uncomfortable. Britain is not keeping pace with peer nations in controlling price rises. This matters because inflation control is supposed to be the primary function of the Bank of England. The institution exists specifically to manage this problem. It is failing at its core purpose, measurably, compared to equivalent institutions in comparable countries.

The Pattern Continues

Three characteristics define British institutional performance in the 21st century:

First, chronic underperformance relative to peer nations on measures that matter to citizens.

Second, selective emphasis on whichever metrics look least bad at any given moment.

Third, persistent refusal to address underlying structural problems that transcend electoral cycles.

The IMF report documents this pattern without commenting on it directly. The Fund upgraded global growth. Britain remains the inflation outlier. These facts exist simultaneously in the same economic landscape.

What This Actually Means

When your inflation is the highest in the industrialised world while your per-capita growth is the lowest in your peer group, you have a fundamental competitiveness problem. Not a temporary policy issue. Not a political dispute about priorities. A structural failure in how your economy functions.

This is not about Brexit or non-Brexit, Labour or Conservative. These are the performance figures under current institutional arrangements, whoever happens to be operating them.

The IMF produces these reports twice yearly. The statistics change marginally. The underlying trajectory remains remarkably consistent. Britain underperforms its peers on the metrics that determine whether ordinary people’s lives improve.

The uncomfortable question is not whether this will be acknowledged. It is whether Britain’s institutions are capable of addressing problems they have proven unable to solve under multiple governments, multiple policy frameworks, and multiple economic conditions.

The data suggests they are not. The response from those institutions suggests they do not intend to try.

The Treasury will highlight that growth statistic. The inflation figures will receive less attention. The per-capita growth numbers will barely feature at all.

This is not spin. This is how decline operates when everyone involved has an incentive to avoid confronting it directly.

The IMF has documented the symptoms. The patient remains in denial. The treatment never begins.

Commentary based on Four big themes as IMF takes aim at UK growth and inflation by Ed Conway on Sky News.