The Motability Machine: When Public Service Becomes Private Profit

How a Disability Support Scheme Became a £14 Billion Car Leasing Empire

Lana Hempsall's investigation into Motability reveals a textbook case of institutional mission drift. What began as essential support for severely disabled individuals has morphed into Britain's largest vehicle leasing operation, operating under the protective umbrella of public benefit while generating substantial private returns.

What they claim: Motability helps disabled people access essential transport.

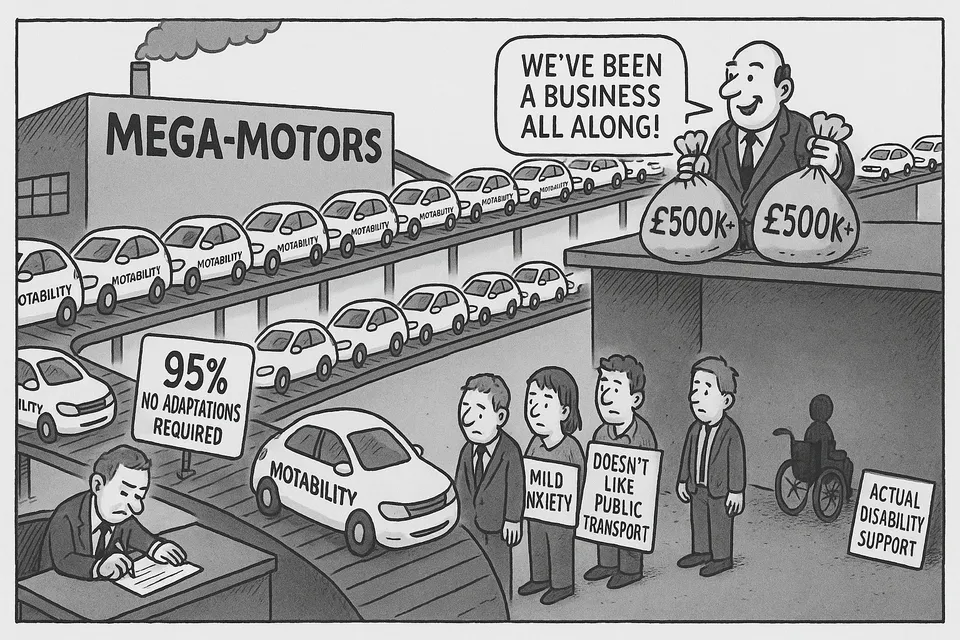

What actually happened: A £14 billion car leasing empire that pays its CEO over £500,000 annually while delivering subsidised vehicles to 815,000 people—despite only 5% requiring disability adaptations.

The Numbers Don’t Lie

The scale of Motability’s transformation is documented in stark statistics. From its 1978 inception as a lifeline for severely disabled drivers, the scheme now operates one in five new cars sold in Britain. Its fleet has grown by 200,000 vehicles in just two years, reaching 815,000 total—a figure that represents not evolution but institutional mutation.

CEO Andrew Miller’s recent defence—“We’ve been a business all along”—inadvertently exposes the core dysfunction. If Motability has “always been a business,” why does it require billions in taxpayer subsidy? If it’s a public service, why does it operate like a mass car dealership?

Mission Creep as Business Model

The original purpose was clear: provide adapted vehicles for people who couldn’t otherwise drive due to severe physical disabilities. Today’s reality reveals institutional capture in action. Only 5% of Motability cars require disability adaptations, yet the scheme continues expanding its customer base through loosened government criteria.

This isn’t accidental drift—it’s systematic expansion. Motability actively markets to potential customers, writing unsolicited letters to people like the article’s author, who lost eyesight in their teens, offering “brand new cars.” When institutions begin hunting for customers rather than serving genuine need, they’ve ceased being public services and become profit centres.

The Accountability Vacuum

Miller’s admission that Motability hasn’t been “strong enough in enforcing key terms” reveals another classic feature of declining institutions: the buck stops nowhere. He blames successive governments for loosening criteria while simultaneously defending his organisation’s explosive growth. This circular responsibility ensures no one is actually accountable for the scheme’s transformation from disability support to mass vehicle subsidy.

Meanwhile, Miller collected over £500,000 for overseeing this expansion. In Britain’s declining institutional landscape, failure often pays better than success, provided you can frame expansion as achievement and mission creep as evolution.

The Costs

Every penny flowing to someone who doesn’t need a subsidised car is a penny not reaching someone who does. This isn’t about deserving versus undeserving—it’s about finite resources and institutional priorities. When a scheme designed for severe disability operates primarily for people requiring no vehicle adaptations, it has fundamentally abandoned its purpose.

The broader pattern is familiar: institutions created to serve genuine public need gradually expanding their remit until they primarily serve themselves. The NHS treating health tourists while citizens wait months for operations. Universities charging £9,000 for degrees worth less each year. Housing associations building executive homes while social tenants live in squalor.

The Choices

Motability’s defenders will claim any restriction is “attacking disabled people.” This emotional blackmail obscures the real choice: continue subsidising a car leasing operation that happens to serve some disabled people, or reform it back into targeted support for those who genuinely cannot access transport otherwise.

The current system serves three groups exceptionally well: car manufacturers selling hundreds of thousands more vehicles annually, Motability executives drawing fat-cat salaries, and people receiving subsidised cars they don’t specifically need. The people it serves poorly are taxpayers funding this expansion and severely disabled people competing for resources with a much larger pool.

Reality Checks

When institutional leaders defend obvious mission creep by claiming they’ve “always been a business,” they’re admitting the game. Motability has become another example of British institutional capture—public money, private profit, and declining service for those who need it most.

The scheme will continue growing until external pressure forces reform, because institutions don’t voluntarily reduce their own size or executive salaries. Meanwhile, the genuine disabled access the car industry’s marketing dream: a captive market of 815,000 subsidised customers, with millions more potentially eligible.

This is how decline accelerates through institutions gradually abandoning their purpose while maintaining their funding. Motability isn’t broken. For its executives and stakeholders, it’s working perfectly.

Commentary based on Motability won’t give up its lucrative business without a fight by Lana Hempsall on The Spectator.