When Failure Pays: The Water Industry's Reward System

How privatized water companies in England profit from underinvestment and rising bills

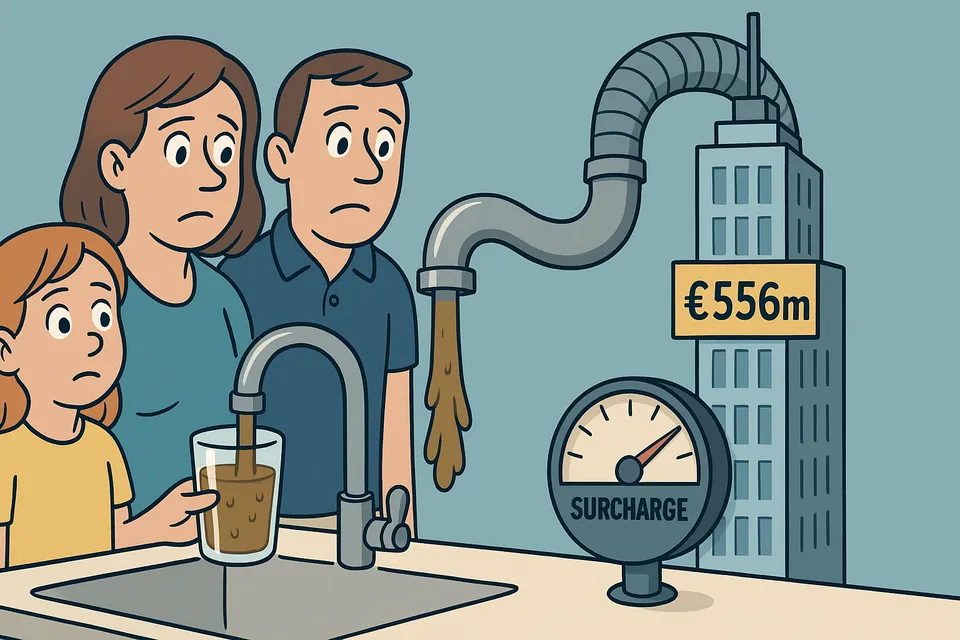

Five English water companies have successfully argued for higher bills to cover infrastructure failures they were supposed to maintain. The Competition and Markets Authority approved an additional £556 million in charges, on top of already planned 36% increases over five years. This comes as serious pollution incidents by water firms jumped 60% in a single year, highlighting a troubling pattern of privatized monopolies profiting from public goods while failing to deliver essential services.

Five English water companies have successfully argued they deserve higher bills because the infrastructure they were supposed to maintain has failed. The Competition and Markets Authority agreed, granting them permission to charge customers an additional £556 million on top of already planned 36% increases over five years. This decision arrives as serious pollution incidents by water firms jumped 60% in a single year.

The logic is instructive: decades of underinvestment in infrastructure now require emergency funding, and the source of that funding is the captive customer base with no alternative supplier.

The Context

Water privatization in 1989 rested on a straightforward promise. Private companies would deliver better service and infrastructure investment than public ownership. Profit incentives would drive efficiency. Shareholders would fund improvements. Customers would benefit from competition and innovation.

Thirty-six years later, the same companies return to regulators explaining they need more money to fix the infrastructure they were supposed to be maintaining all along. The appeal was successful. The customers will pay.

What the Numbers Show

The five companies requested £2.7 billion in additional revenue. The CMA approved £556 million, roughly 21% of what was requested. This represents an extra 3% on bills, or approximately £12 per household annually, serving more than 7 million customers.

These increases come after Ofwat already approved average rises of 36% over the next five years. Water bills will therefore increase by roughly 39% in total for customers of these five companies.

Meanwhile, serious pollution incidents by water companies increased by approximately 60% in one year, according to the Environment Agency. The infrastructure these higher bills are meant to fund has been deteriorating for years while companies operated under private ownership with shareholders and debt obligations.

Water UK’s chief executive noted that eight water firms made losses in 2024. Yet between 1991 and 2019, the privatized water companies paid out £57 billion in dividends to shareholders while loading themselves with £53 billion in debt.

The Pattern

This follows a familiar trajectory in British institutional decline:

- A public asset is privatized with promises of improved service and efficiency

- Companies extract maximum value through dividends and executive pay while minimizing capital investment

- Infrastructure deteriorates to crisis point

- Companies plead poverty and demand customer funding for “essential improvements”

- Regulators grant increases while noting “pressure on household budgets”

- No executives are fired, no shareholders repay dividends, no structural reform occurs

The Thames Water situation epitomizes the endpoint. The company is in such dire financial condition it has deferred its appeal for higher prices until late October while attempting to arrange a rescue package. This is the largest water company in the UK, serving 16 million people. It extracted billions in dividends while accumulating £15 billion in debt. Now it needs saving.

The regulatory system has produced an outcome where failure is rewarded with guaranteed revenue increases while success metrics like pollution prevention deteriorate.

Who Bears The Cost

Citizens Advice notes that people are already “rationing showers and cutting down on laundry” due to high bills. The proposed solution from water company representatives is that shareholders cannot be expected to fund improvements from past profits because “they don’t have to put money into this sector, they don’t even have to put money into this country.”

This framing is remarkable. An industry providing essential infrastructure to a captive customer base, operating under regulatory protection from competition, suggests that shareholders might withdraw their capital if not sufficiently rewarded. The implicit threat: pay up or face even worse service.

The customers cannot withdraw. They have no alternative water supplier. They cannot negotiate prices. They cannot refuse service. This is not a market in any meaningful sense. It is a guaranteed revenue stream with regulatory permission to increase prices when costs rise or infrastructure fails.

The CMA panel noted that water companies’ requests for significant increases were “largely unjustified” but still approved £556 million in additional charges. The gap between “largely unjustified” and “approved anyway” measures the distance between regulatory purpose and regulatory reality.

The Accountability Gap

No mechanism exists to reclaim the dividends paid during the years of underinvestment that created the current crisis. No executive compensation has been clawed back. No shareholders face penalties for the infrastructure decay that occurred under their ownership.

Water Minister Emma Hardy’s response captures the limits of political power in this system: she “expected” every water company to “offer proper support to anyone struggling to pay.” This is hope presented as policy. There is no requirement, no enforcement mechanism, no consequence for companies that fail to provide such support.

The regulatory structure has evolved to protect water companies from the consequences of their decisions while transferring costs to customers who have no choice but to pay. When Kirstin Baker, chair of the CMA expert group, says the panel “worked to keep increases to a minimum,” she describes negotiating the scale of guaranteed price rises for companies that have failed to maintain infrastructure. This is regulatory capture functioning openly.

What Competent Governance Looks Like

A functional system would connect past performance to future permissions. Companies that paid excessive dividends while infrastructure deteriorated would face dividend bans until assets reach acceptable condition. Executives who oversaw infrastructure decay would not receive bonuses. Shareholders who extracted billions would contribute to repair costs before customers pay extra.

A functional regulator would have prevented the crisis through enforcement of maintenance standards, not negotiated price increases after failure became undeniable. Pollution incidents increasing 60% in one year represents a regulatory failure as much as a corporate one.

A functional political system would have reformed water privatization when the model’s failures became apparent years ago. Instead, the same structure persists with the same incentives producing the same outcomes.

The Bigger Picture

The water industry exemplifies how institutional decline functions in modern Britain. A privatized system designed to deliver better outcomes through market incentives instead produces deteriorating service, environmental damage, and guaranteed price increases. The regulatory bodies meant to protect customers negotiate the terms of failure rather than preventing it.

This is not unique to water. Energy, rail, telecommunications, and other privatized utilities follow similar patterns. Private profit during good times, socialized losses during bad times, customers as the guaranteed funding source for fixing what was never properly maintained.

The competence question is now unavoidable. The current system does not work. The evidence is measured in sewage discharge, pollution incidents, and infrastructure failure. Yet the same structure continues with minor modifications, the same arguments are accepted, and the same costs are transferred to households already cutting back on essential water use.

When citizens are rationing showers to afford water bills that are rising to pay for infrastructure that should have been maintained by companies that paid billions to shareholders, the system has failed at the most basic level. When regulators respond by approving more increases while noting the costs are “largely unjustified,” institutional dysfunction is complete.

Britain once built infrastructure that lasted generations. Now it cannot maintain what it inherited. The water crisis is not an anomaly. It is the model.

Commentary based on Water bills to rise further for millions after appeal by Faarea Masud on BBC News.